Referential and Reviewed International Scientific-Analytical Journal of Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Faculty of Economics and Business

Shaping the Future of Georgia’s Healthcare Business: Market Trends, Development Strategies, and Revenue Diversification

doi.org/10.52340/eab.2025.17.03.09

Over the past two decades, Georgia’s healthcare sector has undergone significant transformation, marked by evolving service delivery models and an increasing role of the private sector. This article analyzes key trends in the development of healthcare businesses in Georgia, drawing on statistical and analytical data collected between 2010 and 2024.

The study employs a mixed-method approach—integrating quantitative and qualitative analysis with comparative assessments, trend evaluations, and strategic frameworks such as Porter’s Five Forces and the WHO Health Systems Strengthening model. This comprehensive methodology enables a thorough and multidimensional exploration of Georgia’s healthcare business landscape. International best practices are examined through case studies from the Baltic (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia) and Scandinavian (Finland, Denmark) regions. Particular emphasis is placed on the expansion of private investment, the potential for medical tourism, the adoption of digital technologies, and the strategic optimization of human resources.

Current market trends in Georgia’s healthcare sector highlight the expansion of private clinics and diagnostic centers, a surge in medical tourism – particularly in dentistry, cosmetology, reproductive medicine, and oncology – the integration of digital healthcare solutions such as telemedicine, electronic medical records, and AI-driven diagnostics, and the diversification of financial models, including broader insurance coverage.

High-potential growth areas include oncology, cardiology, reproductive health services, rehabilitation, and wellness/medical tourism. Notably, infrastructure gaps in regional areas present valuable opportunities for private sector investment.

Key challenges facing the sector include regulatory instability, workforce shortages – especially among nursing staff – insufficient mechanisms for continuous quality control, low levels of patient trust, and limited access to services for socially vulnerable populations.

This study serves as a practical resource for healthcare policymakers, industry professionals, private investors, and academic researchers seeking a comprehensive and strategic analysis of modern healthcare business development in Georgia.

In the short term, key priorities include streamlining licensing procedures, mandating accreditation, and enhancing insurance models to improve coverage and efficiency. Medium-term goals focus on strengthening medical education and expanding public-private partnership (PPP) initiatives to foster innovation and infrastructure development. As a long-term strategy, Georgia aims to position itself as a regional hub for high-quality medical services and health tourism. Achieving this vision will require full alignment with European Union and World Health Organization standards.

Georgia’s healthcare sector stands at a pivotal juncture. Its future success hinges on consistent policymaking, robust collaboration between public and private stakeholders, and a long-term strategic vision that balances quality, accessibility, and financial sustainability.

Keywords: Business models, model transformation, private clinic, healthcare business, promising sector, medical tourism, innovation, strategy.

JEL Codes: I11, I12, I13, I15, I18, L22, M21, O33

Introduction

In the transformative landscape of the 21st century, healthcare is no longer viewed solely as a social service – it has emerged as a vital pillar of economic activity, innovation, and investment development. In Georgia, where the healthcare sector has historically oscillated between rigid state control and phases of liberalization, its evolution from a business perspective has garnered growing interest among academics and industry professionals alike.

Since gaining independence in 1991, Georgia’s healthcare system has undergone profound changes. Inheriting an overextended, underfunded, and inefficient Soviet-era model, the country embarked on sweeping reforms in the early 2000s. Privatization and deregulation initiatives catalyzed a wave of private investment, the establishment of modern hospital infrastructure, and the gradual adoption of international accreditation standards such as TEMOS and Joint Commission International (JCI). Today, healthcare plays an increasingly prominent role in Georgia’s service economy, intersecting with key sectors like tourism, education, and digital innovation.

Healthcare business development in Georgia is shaped by a complex set of processes: the advancement of public-private partnership models, alignment with international standards, expansion of medical tourism, integration of cutting-edge technologies, response to workforce shortages, and the geographic broadening of service delivery. A diverse array of stakeholders – including medical institutions, investors, regulatory bodies, and international donor organizations actively contribute to these transformative efforts.

The current market landscape presents a nuanced blend of opportunity and uncertainty. Georgia’s strategic location at the intersection of Europe and Asia, combined with its liberal visa policies and competitive pricing, positions the country as a promising destination for medical tourism and cross-border patient inflow. However, the sector continues to face significant challenges. These include inconsistent quality standards, underdeveloped digital infrastructure, shortages of specialized medical personnel, and high out-of-pocket costs that restrict access for vulnerable populations. Additionally, geopolitical instability in the broader region, along with domestic political fluctuations, poses risks to investor confidence in the healthcare industry. Given these dynamics, a multifactorial analysis of prevailing trends is essential – one that draws on empirical data and comparative methodologies to inform strategic decision-making.

Emerging global healthcare trends – such as the rise of telemedicine, personalized medicine, and integrated care models – are increasingly shaping local market strategies. Georgia’s growing adoption of electronic health records and digital diagnostics signals a readiness for deeper digital health integration. Moreover, the post-pandemic era has highlighted the critical importance of supply chain resilience, domestic production of medical supplies, and cross-border health security partnerships.

This study aims to evaluate the current state and evolving dynamics of healthcare business development in Georgia, with a comparative lens on international practices. Special attention is given to the Baltic countries (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia) and the Scandinavian model (Finland, Denmark), which share similar systemic origins but have followed distinct paths of transformation. These reference models offer valuable insights for assessing Georgia’s strategic prospects – not only through internal sectoral analysis but also within the broader global economic and social context.

The paper is guided by three central questions:

1. What are the dominant trends shaping the healthcare business landscape in Georgia?

2. Which sub-sectors present the highest growth potential for domestic and foreign investors?

3. What policy interventions are necessary to ensure that market expansion leads to improved health outcomes and greater social equity?

Through the analysis of statistical data, policy reviews, and expert perspectives, this study contributes to both academic discourse and practical policymaking in the Georgian healthcare sector.

Literature Review

1. Global Trends in Healthcare Business

Over the past two decades, the global healthcare business environment has undergone rapid transformation, driven by demographic shifts, technological advancements, and changing consumer expectations. Four key trends – telemedicine, medical tourism, digital health, and integrated care models – are particularly relevant to Georgia’s evolving healthcare sector.

• Telemedicine has transitioned from a niche service to a mainstream healthcare solution, a shift accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2022), more than 70% of countries have incorporated telemedicine into their health systems, with usage rates doubling in high- and middle-income nations between 2019 and 2021. Telemedicine presents clear business advantages: lower operational costs, expanded geographic reach, and the ability to serve rural and underserved populations without the need for costly infrastructure investments (Smith & Thomas, 2021).

• Medical tourism has grown into a $70–100 billion global industry (Global Wellness Institute, 2022), propelled by disparities in cost, access, and quality of care across countries. The sector is increasingly segmented into high-end elective procedures—such as cosmetic surgery and fertility treatments—complex tertiary care, and wellness or preventive health packages. Emerging markets, especially in Eastern Europe and Asia, have capitalized on competitive pricing and cultural proximity to attract international patients (Connell, 2021).

• Digital health encompasses a broad range of technologies, including electronic health records (EHRs), AI-powered diagnostics, wearable devices, and predictive analytics. The global digital health market is projected to grow from $211 billion in 2022 to over $550 billion by 2028 (Grand View Research, 2023). Beyond cost efficiencies, digital health enhances care coordination, supports data-driven clinical decisions, and fosters greater patient engagement – key components of a competitive and sustainable healthcare business model.

• Integrated care models represent a structural shift aimed at bridging the gaps between primary, secondary, and tertiary care. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2021), integrated care reduces service duplication, improves outcomes for chronic conditions, and aligns with value-based healthcare principles. From a business perspective, integration opens new avenues for collaboration and revenue-sharing among healthcare providers, insurers, and ancillary service organizations.

2. Regional Context: Post-Soviet Healthcare Reforms

Since the early 1990s, post-Soviet states have undertaken diverse healthcare reforms, offering a valuable comparative framework for assessing Georgia’s development.

The Baltic states – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – swiftly transitioned to social insurance models aligned with European Union standards. Estonia, for example, launched a centralized electronic health record (EHR) system in 2008 and now ranks among Europe’s most digitally advanced health systems (Kattel & Mergel, 2019). Baltic reforms prioritized strengthening primary care, implementing transparent procurement processes, and establishing quality accreditation mechanisms, which collectively improved health outcomes and attracted private investment.

Eastern European countries such as Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary adopted mixed financing models featuring mandatory health insurance and robust private sector participation. These systems retained relatively strong public hospital networks compared to the Baltics but increasingly rely on private clinics for diagnostics, dental services, and elective procedures. Medical tourism has emerged as a key growth sector, particularly in Poland and Hungary (Balaz & Williams, 2020).

In contrast, healthcare reforms in the South Caucasus have been uneven. Armenia’s system remains predominantly publicly financed but suffers from chronic underfunding, with private investment largely concentrated in the capital, Yerevan. Azerbaijan has directed oil revenues toward hospital infrastructure development but continues to lag in insurance reform and quality assurance. Georgia, meanwhile, pursued one of the most aggressive privatization strategies in the post-Soviet region, selling or leasing the majority of hospitals to private operators by the mid-2000s. While this approach accelerated infrastructure modernization, it also introduced challenges related to equitable access and regulatory oversight (Chanturidze et al., 2015).

3. Georgia-Specific Studies and Trends

Georgia’s healthcare business landscape has been shaped by three pivotal developments: the influx of private investment, progressive insurance reforms, and the adoption of international accreditation standards.

• Private investment accelerated following the 2007 wave of hospital privatizations. According to the National Statistics Office of Georgia (GeoStat, 2023), private healthcare investment grew at an annual rate of 8–10% between 2015 and 2022, with a strong concentration in Tbilisi and select regional centers. Foreign investors from Turkey, Israel, and Gulf countries have entered the market, primarily targeting high-margin specialties such as cardiology, oncology, and fertility services.

• Insurance reform has followed an iterative path. The launch of the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) program in 2013 significantly expanded access to care but placed growing pressure on public budgets and private providers. While UHC has increased patient volumes, low reimbursement rates continue to create tension between cost containment and quality improvement. Research by Gotsadze et al. (2021) underscores the importance of introducing tiered benefit packages and fostering public–private partnerships to ensure long-term sustainability.

• The uptake of international accreditation has been gradual yet pivotal in positioning Georgia as a competitive destination for medical tourism. As of early 2025, accreditation has become mandatory for all healthcare providers participating in the Universal Health Coverage Program (UHCP) – a landmark policy aimed at standardizing quality across both public and private institutions. Numerous Georgian hospitals have secured international certifications such as TEMOS, Joint Commission International (JCI), and AACI, significantly boosting their credibility among foreign patients.

• Shifts in patient demand reflect broader societal changes, including rising expectations from the middle class, increased willingness to pay for private healthcare services, and growing interest in preventive and wellness-oriented care. Despite these trends, out-of-pocket expenditure continues to account for more than 50% of total health spending, highlighting the critical role of private providers in addressing unmet healthcare needs (WHO Global Health Expenditure Database, 2023).

4. Theoretical Frameworks

Porter’s Five Forces in Healthcare

Porter’s model (1980) provides a valuable framework for analyzing competitive dynamics within Georgia’s healthcare sector:

• Threat of New Entrants: Moderate Licensing regulations are relatively accessible, but the high capital requirements for establishing advanced medical facilities pose a significant barrier to entry.

• Bargaining Power of Suppliers: High Georgia remains heavily dependent on imported pharmaceuticals and medical equipment. Currency fluctuations and limited domestic production amplify supplier influence and impact provider margins.

• Bargaining Power of Buyers: Increasing With greater access to health information and expanding medical tourism options, patient expectations for quality and service are rising, enhancing consumer leverage.

• Threat of Substitutes: Growing Alternatives such as telemedicine and cross-border healthcare services are gaining traction, offering patients more flexible and cost-effective treatment options.

• Industry Rivalry: High in Urban Centers, Lower in Rural Areas Intense competition among private hospitals in cities like Tbilisi contrasts with limited provider presence and lower rivalry in rural regions.

Health Systems Strengthening (WHO Framework)

The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies six core building blocks of a health system: service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, access to essential medicines, financing, and leadership/governance. When applied to Georgia’s healthcare landscape, the following assessment emerges:

• Strengths: Modernization of service delivery, expansion of the private healthcare sector, Growth in health information systems.

• Weaknesses: Shortages in the health workforce, particularly among medical specialists, limited healthcare coverage in rural regions, heavy reliance on imported pharmaceuticals and medical supplies.

• Opportunities: Integration of digital technologies across the health system, expansion of telehealth services to improve access, alignment of procurement practices with European Union standards

• Threats: Political instability and inconsistent policy implementation

Triple Aim in Healthcare

The Triple Aim (Berwick et al., 2008) underscores three key objectives: enhancing patient experience, reducing per capita healthcare costs, and improving population health. In the context of Georgia:

• Patient Experience: Improving in accredited private facilities, yet remains uneven across the public sector.

• Cost Efficiency: Gains have been achieved through private sector efficiency; however, out-of-pocket expenses continue to be high.

• Population Health: The burden of chronic diseases remains significant, and preventive care is still underutilized.

5. Synthesis of Literature

Global and regional evidence indicates that Georgia’s healthcare business development reflects broader trends – namely, privatization, digital integration, and cross-border patient mobility. Unlike the Baltic states, which paired privatization with robust public oversight and EU integration, Georgia has leaned more heavily on market-driven approaches. This has led to notable infrastructure modernization but has also resulted in inconsistent quality assurance.

International trends – particularly in digital health and integrated care—present promising avenues for Georgia to strengthen both its healthcare competitiveness and health outcomes. Aligning national policies with WHO health system strengthening priorities and the Triple Aim framework could help close existing gaps. Applying Porter’s Five Forces reveals strategic opportunities, such as developing local manufacturing for medical supplies and establishing regional telemedicine networks, to bolster resilience against external shocks.

In summary, the literature suggests that Georgia’s healthcare business sector stands at a strategic inflection point. The coming decade will be shaped by the country’s ability to adopt international best practices, secure sustainable financing, and align policy incentives with both investor priorities and public health objectives.

Research Methodology

As outlined above, this research employs a multi-instrumental, mixed-methodological approach, enabling a comprehensive and systematic exploration of the topic. Specifically, it integrates quantitative analysis of secondary data with qualitative insights derived from expert interviews. This design reflects the complex nature of healthcare business development in Georgia, which encompasses both measurable market dynamics and nuanced policy, regulatory, and operational factors that require contextual interpretation.

The quantitative component examines key indicators such as market size, investment flows, service utilization rates, and accreditation adoption, using time-series data sourced from national and international databases.

The qualitative component captures the perspectives of key industry stakeholders – including healthcare executives, policymakers, medical professionals, and accreditation consultants – on prevailing challenges, emerging opportunities, and strategic priorities.

The research methodology incorporates the following tools:

Document Analysis

At the initial stage of the research, a comprehensive review was conducted of documentation related to health sector reforms, legislation, state programs, and reports from international institutions such as the WHO, World Bank, and OECD. This documentary analysis enabled the assessment of system development stages, key policy decisions, and regulatory frameworks.

Quantitative Analysis

To identify trends, official statistical data were sourced from GeoStat, the Ministry of Health, the NCDC, and annual reports from private clinics. Data processing was performed using Excel and SPSS. Key variables analyzed included the number of clinics, private sector share, volume of state funding, medical tourism indicators, and other relevant metrics. Trends in investment flows, patient volumes, accreditation adoption, and insurance coverage were examined using descriptive statistics and compound annual growth rates (CAGR).

Comparative Analysis

The study employs a comparative analysis approach, positioning Georgia’s healthcare business model alongside those of other post-Soviet countries—particularly the Baltic states. This method facilitates the evaluation of development and integration trajectories within both regional and global contexts.

Expert Interviews

The qualitative component of the research involved conducting semi-structured interviews with key representatives from the healthcare sector, including clinic managers, healthcare policy experts, members of business associations, and investors. These interviews aimed to provide a deeper understanding of the system and to identify current challenges and emerging opportunities.

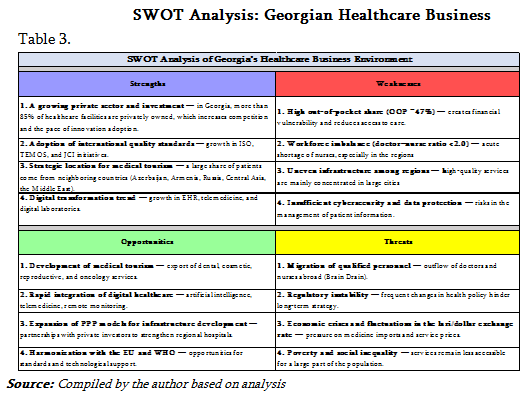

SWOT Analysis

In the final stage, a SWOT analysis was conducted to synthesize the findings within a strengths–weaknesses–opportunities–threats framework. This approach helped assess internal market capabilities and external influencing factors. Strengths and weaknesses were drawn from interview insights and domestic performance indicators, while opportunities and threats were identified through mapping global and regional trends.

Data Collection Procedures

• Secondary Data: Data were extracted directly from official databases, publications, and peer-reviewed journal articles spanning the period 2010–2024, ensuring coverage of both long-term trends and recent developments. The data cleaning process involved cross-verification across multiple sources to resolve inconsistencies—such as discrepancies between Ministry of Health and WHO reporting.

• Expert Interviews: Semi-structured interviews with 23 key informants:

15 executives from private hospitals and diagnostic centers.

3 officials from MoH and regulatory agencies.

2 representatives from international accreditation organizations.

3 independent healthcare policy analysts. Interviews were conducted in person and via secure video conferencing between March and May 2024, each lasting 45–60 minutes.

Ethical Considerations

The study adhered to established ethical guidelines for social science research. Interview participants received an information sheet and consent form detailing the study’s purpose, confidentiality protocols, and their rights to voluntary participation. All interview data were anonymized to safeguard the identities of individuals and organizations involved.

Limitations

• The study’s reliance on secondary data may be subject to reporting biases and gaps, particularly within private sector statistics.

• The limited interview sample size may not fully reflect the diversity of perspectives across Georgia’s healthcare ecosystem.

• External factors – such as geopolitical instability – could impact observed trends in ways that fall outside the study’s control or predictive scope.

Current State of Georgia\'s Healthcare Business

In today’s global economy, the healthcare sector stands out as one of the most rapidly evolving industries, with private sector engagement and market liberalization playing a critical role in shaping service quality and accessibility. Over the past decades, Georgia has implemented a series of reforms that have significantly transformed its healthcare business environment—bringing both new opportunities and complex systemic challenges.

Since 2012, the healthcare landscape in Georgia has experienced substantial shifts, marked by liberalization, privatization, and reforms in healthcare financing. These changes have elevated the role of private providers in service delivery. This study aims to examine the internal dynamics of Georgia’s healthcare business and benchmark them against high-performing systems in the Baltics and Scandinavia, with the goal of identifying strategic pathways for sustainable growth.

In the post-Soviet era of the 1990s, private initiatives began to play an increasingly prominent role in Georgia’s healthcare system amid a backdrop of reduced public funding. This period laid the groundwork for the emergence of private medical institutions, although the sector lacked regulatory oversight and a coherent strategic vision.

Reforms initiated in 2007 marked a turning point, as the management and ownership of medical institutions were transferred to the private sector. This shift significantly altered the healthcare business environment: clinics gained full entrepreneurial autonomy, competition intensified, and service diversification expanded. However, these developments also underscored the growing need to balance service quality with financial accessibility.

The launch of the Universal Healthcare Program in 2013 substantially increased the state’s responsibility for ensuring citizens’ access to healthcare. Despite this expansion of public involvement, the private sector continues to dominate clinic ownership and management. As a result, Georgia’s healthcare system now operates as a hybrid model, characterized by interdependence between public and private interests.

Beginning in 2023, the Georgian Ministry of Health introduced mandatory quality standards and required international accreditation for hospitals and clinics receiving reimbursement through the Universal Health Insurance Program. Facilities must now demonstrate compliance with internationally recognized benchmarks.

Also in 2023, the government implemented a new financing model based on Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRG), aimed at enhancing system efficiency and sustainability. While this model standardizes reimbursement for similar diagnoses and treatments, it presents challenges for healthcare businesses. Specifically, it does not account for variations in case complexity or cost, meaning that even resource-intensive treatments are reimbursed at a uniform base rate.

Currently, Georgia’s healthcare business is in a phase of development and stabilization. However, several key challenges persist:

• Ensuring the standardization of service quality and patient safety

• Addressing the shortage of qualified healthcare professionals

• Integrating digital technologies and fostering innovation

• Unlocking the full potential of medical tourism

• Strengthening the regulatory framework governing the private sector

In recent years, Georgia’s healthcare sector has undergone notable transformations, as evidenced by shifts in the number of clinics, bed capacity, and evolving business models.

Healthcare Market Structure and Players

According to 2024 data, both state and private healthcare organizations operate in Georgia, with the private sector holding a dominant position. Of the approximately 280 clinics currently in operation, 85–90% are privately owned. While the total bed capacity across these clinics is around 18,500 units, average bed occupancy stands at only 50%, highlighting inefficient utilization of infrastructure (GeoStat).

In 2024, 1.617 billion GEL was allocated to the universal healthcare program. In comparison, 2023 saw an expenditure of 27 million GEL more than the 2024 allocation. That year, the program was initially allocated 980 million GEL, but actual spending reached 1.062 billion GEL. Five years earlier, in 2019, the program received a total allocation of 829 million GEL (GeoStat).

In urban areas, primary healthcare services are predominantly delivered by private providers, whereas in rural regions, state-funded solo practitioners are the main source of care (Health Systems in Action Insight Series, 2024).

Key Market Players

In Georgia, the hospital sector is predominantly privately owned. According to 2021 data, 86% of hospitals are privately operated, while only 14% belong to the public sector. As of 2024, the country has 5.6 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants (BM.GE).

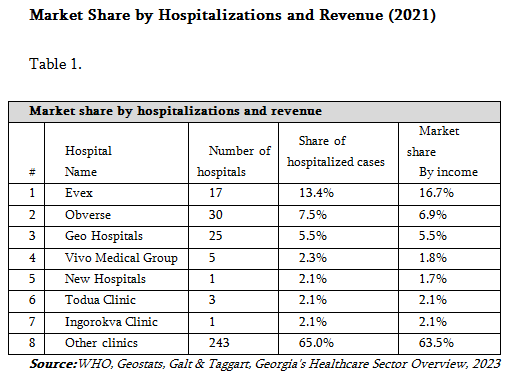

The market share distribution among leading players in Georgia’s healthcare sector can be evaluated using various indicators, including the number of hospital beds, hospitalization rates, and revenue figures. Table 1 below presents the 2021 data illustrating this distribution:

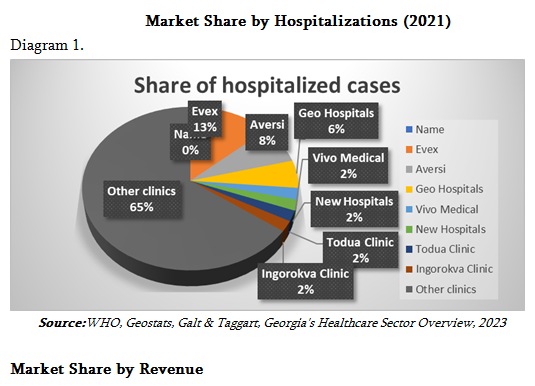

Market Share by Hospitalization Rate

Hospitalization rates in Georgia are 3 to 4 times higher than the European average, reflecting an excessive demand for hospital services. This trend may be attributed to the underdevelopment of primary healthcare and a widespread tendency among the population to self-medicate (Curatio International Foundation, 2022).

Despite an increase in the number of hospital beds, occupancy rates remain low. In 2021, the average bed occupancy rate was 55%, significantly below the European Union average of 77% and the CIS average of 83.4% (BM.GE).

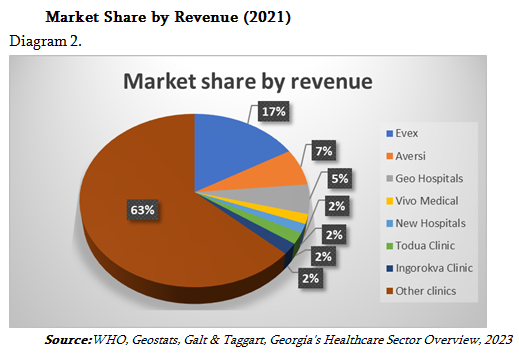

Market Share by Revenue

Over the past decade, revenues in Georgia’s healthcare sector have shown consistent growth, driven by rising population demand and increased private investment. The market is primarily divided into three key segments:

• Hospital Services: This segment accounts for approximately 55–60% of total market revenues and includes both major hospital chains—such as Evex, Aversi, and Vivamed—and regional clinics.

• Outpatient/Polyclinic Services: Representing 20–25% of market revenues, this segment is dominated by small clinics. These facilities typically offer lower pricing but handle a high volume of patient visits.

• Pharmaceutical Products and Laboratory Services: Contributing around 15–20% of revenues, this segment encompasses medicines, diagnostic tests, and laboratory analyses. Its growth is fueled by a rising prevalence of chronic diseases and the expansion of medical tourism.

The market share of major healthcare networks in Georgia is distributed as follows:

• Evex Hospitals: The largest private hospital operator in the country, offering comprehensive medical services nationwide. As of 2025, Evex owns 17 hospitals across Georgia’s main regional cities, holding a market share of 16.7%.

• Aversi Clinic: Operating 13 branches and 22 laboratories as of 2025, Aversi serves approximately 2,000 patients daily, with a market share of 6.9%.

• Geo Hospitals: A nationwide network providing both primary and specialized care, accounting for 5.5% of the market.

• Other Providers: Collectively represent the remaining 70.9% of the market

Market Challenges

The Georgian healthcare sector is well diversified in terms of market participants and share distribution, resulting in a high level of competition. Financially, the sector has demonstrated strong performance: total revenue rose from 1.2 billion GEL in 2018 to 1.8 billion GEL in 2021. In 2022, total healthcare expenditures reached 4.1 billion GEL—an increase of 72% compared to 2013. In 2021, boosted by pandemic-related funding, EBITDA margins climbed to 25%, while profit margins reached 17%. However, following the end of the pandemic, COVID-19-related spending declined in 2022 (Geostat, 2023).

Between 2013 and 2022, the expansion of the Universal Healthcare Program significantly reduced the population’s out-of-pocket health spending—from 65% in 2013 to 43% in 2022. During the same period, the share of private health insurance dropped from 14% to 7%, while the government’s contribution increased from 20% to 50%.

Demand for healthcare services is closely tied to demographic trends. Although Georgia’s population has been declining over the past decade, 2022 saw a temporary rise in migration due to the war in Ukraine. Nonetheless, ongoing youth emigration and low birth rates continue to exert downward pressure on healthcare demand.

Structural Overview of Healthcare Business

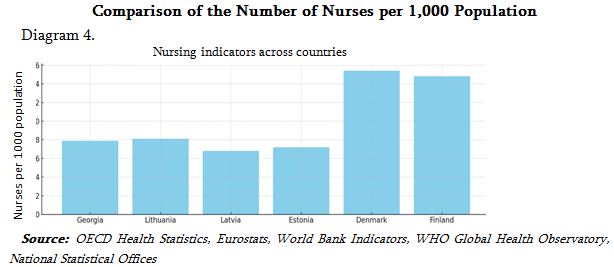

Between 2013 and 2021, Georgia saw an increase in both the number of healthcare providers and hospital beds. However, the average bed occupancy rate remained low at 50%, pointing to inefficient resource utilization. Although the number of medical personnel grew during this period, the nurse-to-doctor ratio remains low at 0.98, suggesting a shortage of nursing staff and potential implications for the quality of patient care.

Structural Snapshot of the Healthcare Business

• Healthcare Spending: In 2023, healthcare expenditures accounted for 8.2% of Georgia’s GDP, up from 6.8% in 2015 (Georgia Country Health Profile, 2023).

• Private and Out-of-Pocket Spending: Private spending makes up 56% of total health expenditures, with out-of-pocket payments comprising 47%, highlighting ongoing financial vulnerability among the population (WHO Global Health Expenditure Database, 2023).

• Growth of Private Clinics: The number of private clinics rose from 145 in 2015 to 280 in 2024, reflecting significant expansion in the private healthcare sector (Geostat, Health Institutions Annual Report, 2024).

Staff and Infrastructure

• The doctor-to-population ratio in Georgia stands at 4.5 per 1,000 inhabitants, exceeding the WHO minimum. However, significant disparities persist between urban and rural areas (WHO Global Health Observatory, 2023).

• The nursing shortage remains a critical issue, with only 1.8 nurses per doctor—well below the EU average of approximately 3.5 (OECD Health Workforce Statistics, 2023).

• Investment in digital healthcare has surged by 160% since 2018, reflecting growing interest in eHealth solutions (MoH, eHealth Progress Report, 2023).

Investments and Growth Sectors

• Medical tourism generated $125 million in revenue in 2023, with a compound annual growth rate of 10–12% (GNTA, Health and Wellness Tourism Trends Report, 2023).

• High-performing segments include reproductive clinics, cosmetic surgery, and dentistry (Enterprise Georgia, Sectoral Review on Medical Services Export, 2023).

• Public-private partnership (PPP) models have played a key role in advancing regional hospital development (PPP Health Projects Report, 2022; World Bank Group – Georgia PPP Framework Review, 2021).

Regulatory Inconsistencies

• Frequent policy changes—particularly in insurance tariffs and licensing requirements—create uncertainty for investors. Stakeholders also report delays in equipment approvals and a lack of clear guidelines for digital and AI-enabled healthcare services.

Comparative Analysis of Georgia with the Baltic and Scandinavian models

The selection of Baltic countries (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia) and Scandinavian model states (Finland, Denmark) for comparative analysis is grounded in historical, institutional, and systemic parallels that are highly relevant to evaluating the development of Georgia’s healthcare system.

The Baltic states exemplify former Soviet republics that have successfully transitioned to European-style hybrid healthcare systems since the 1990s. These systems combine public funding, robust primary care, and the integration of digital technologies (OECD, 2019; WHO, 2022). Like Georgia, they emerged from a deep systemic crisis, but EU membership and structural reforms enabled them to build stable, results-oriented healthcare models (World Bank, 2020).

Finland presents a particularly compelling case due to its unique geopolitical and historical trajectory. Although under Soviet influence throughout much of the 20th century, Finland managed to break away economically and institutionally, embedding itself within the Scandinavian welfare model. Its experience demonstrates that a country with Soviet heritage can successfully establish a universal healthcare system grounded in equity and local self-governance (Kangas, 2010; OECD, 2023).

Denmark stands as a classic example of a Scandinavian welfare state, where healthcare is fully funded through high tax revenues and access to both primary and specialized services is free for all citizens. Denmark’s model showcases how efficient public resource management can be harmonized with high-quality service delivery—an essential benchmark for modern economies (Esping-Andersen, 1990; European Observatory on Health Systems, 2021).

For Georgia, the Baltic experience is particularly relevant, given shared economic, historical, and structural contexts. Finland and Denmark, meanwhile, serve as aspirational models, illustrating how healthcare can evolve from a limited service into a universal social guarantee.

By comparing both groups, Georgia can chart a strategic roadmap that balances short-term adaptation—drawing from the Baltic model—with long-term transformation inspired by Scandinavian principles.

Currently, Georgia’s healthcare business environment is attractive due to its open market, simplified licensing procedures, and expanding medical tourism. However, key challenges remain: ensuring equitable access, retaining qualified personnel, and addressing underfunding in rural healthcare. The experiences of the Baltic and Scandinavian countries suggest that Georgia could significantly improve outcomes through increased public investment, a comprehensive national workforce strategy, and integrated service delivery models.

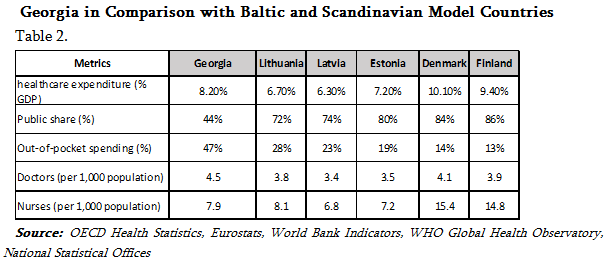

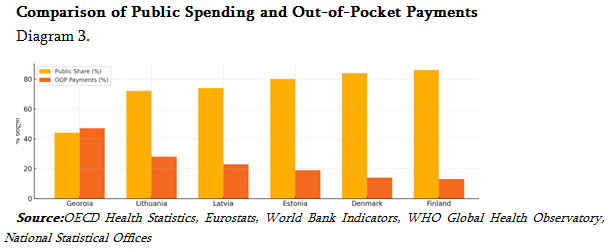

The data presented in Table 2 clearly highlight the structural differences between Georgia and the comparison countries in healthcare financing models, human resource allocation, and out-of-pocket payment rates.

Healthcare Expenditure as a Percentage of GDP (% GDP)

Georgia allocates 8.2% of its GDP to healthcare-more than any of the three Baltic countries (Lithuania: 6.7%, Latvia: 6.3%, Estonia: 7.2%) but less than countries following the Scandinavian model (Denmark: 10.1%, Finland: 9.4%).

Despite Georgia’s relatively high healthcare spending, this investment does not translate into adequate quality or accessibility. This discrepancy stems from inefficient budget allocation and the dominant role of the private sector.

Share of Public Spending

In Georgia, only 44% of healthcare expenditure is publicly financed—a significantly lower proportion than in the comparison countries. In the Baltic states, public financing ranges from 72% to 80%, while in Scandinavian countries it reaches 84% to 86%.

This low public share means a substantial portion of the Georgian population must cover healthcare costs out of pocket. As a result, access to services becomes unequal, and the financial burden increases the risk of poverty due to medical expenses.

Share of Out-of-Pocket Payments

Out-of-pocket healthcare payments by Georgian citizens account for 47% of total health expenditures-nearly twice the rate seen in the Baltic countries (Lithuania – 28%, Latvia – 23%, Estonia – 19%) and more than three times higher than in Scandinavian countries (Denmark – 14%, Finland – 13%). Such high out-of-pocket (OOP) costs in Georgia are linked to low-income populations forgoing medical services, which negatively affects overall health outcomes.

Number of Doctors per 1,000 Population

Georgia has 4.5 doctors per 1,000 people-the highest among the countries compared (Denmark – 4.1, Finland – 3.9, Baltic countries – 3.4 to 3.8). However, despite the high physician density, challenges persist due to uneven regional distribution, excessive concentration in urban areas, and doctor overload caused by a shortage of nursing staff.

Number of Nurses per 1,000 Population

Georgia’s nurse ratio stands at 7.9 per 1,000 population, which is significantly lower than in Scandinavian countries (Denmark – 15.4, Finland – 14.8) and slightly below the Baltic average of 7.3. This disparity highlights an imbalance in the nurse-to-doctor ratio: Georgia has only 1.8 nurses per doctor, whereas Scandinavian countries maintain a ratio of approximately 3.5 to 4. The shortage of nurses in Georgia hampers service continuity, compromises care quality, and places excessive workload on physicians.

Structural Picture of the Georgian Healthcare Business in an International Context

Comparative analysis indicates that Georgia’s healthcare sector demonstrates a moderate level of financial activity. However, the allocation and structure of these resources differ markedly from the more effective systems seen in the Baltic and Scandinavian models (see Diagram #3).

Although Georgia allocates a higher percentage of GDP to healthcare (8.2%) than Lithuania (6.7%) and Latvia (6.3%), this spending is not matched by sufficient public support or social protection mechanisms. The predominance of the private sector and the financial burden on individuals – evidenced by the 47% out-of-pocket payment rate – pose significant challenges to social equity and universal healthcare access.

In contrast to Georgia, Scandinavian countries such as Denmark and Finland have successfully adopted strong public funding and a nurse-centered care model. This approach enables a continuous and integrated healthcare system that reduces hospital admissions, expands access to preventive services, and improves overall population health outcomes.

The Baltic states – also former members of the Soviet Union – represent hybrid models where private initiatives and public strategies evolve in tandem. Their achievements in primary healthcare reform, the integration of digital health solutions, and the steady reduction of out-of-pocket payments demonstrate that even heavily burdened systems can be transformed through consistent and well-designed policies.

An analysis of Georgia’s medical workforce reveals a critical imbalance: while the country has the highest number of doctors among comparable nations, a significant shortage of nurses (see Diagram #4) undermines the system’s effectiveness. This disparity creates structural inefficiencies, places excessive strain on physicians, and impedes the shift toward team-based care – one of the core principles of modern healthcare delivery.

Opportunity Sectors

Oncology

Oncology in Georgia is positioned for significant growth, driven by rising cancer incidence and the current reliance on outbound medical travel for advanced treatments. Investments in linear accelerators, PET scanners, and targeted therapy programs present opportunities to retain domestic patients and attract international clients seeking high-quality care.

Cardiology

Georgia has established a strong regional reputation in interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery. Sustained demand is fueled by the high prevalence of cardiovascular diseases across the Caucasus and Central Asia. With strategic marketing, cardiology services could be elevated as a flagship offering in Georgia’s medical tourism portfolio.

Fertility Clinics (IVF and ART)

Georgia’s liberal legal framework in reproductive medicine—including permissive surrogacy laws—makes it a highly attractive destination for international clients, particularly from countries with restrictive regulations. This segment benefits from premium pricing and demonstrates high rates of repeat visits and referrals, underscoring its potential for continued growth.

Rehabilitation Medicine

Georgia faces a notable shortage of post-surgical, neurological, and sports rehabilitation facilities. Strategic investment in integrated rehabilitation centers could address unmet domestic needs while also serving as a valuable extension for medical tourism offerings.

Wellness Tourism

Despite Georgia’s rich natural spa resources – such as sulfur baths, Borjomi springs, and Tskaltubo resorts – the sector remains underdeveloped within the global wellness tourism landscape. By integrating these assets with preventive healthcare and corporate wellness programs, Georgia could unlock a lucrative hybrid market.

Infrastructure Gaps for Private Investment

• Rural Diagnostic Access: Advanced diagnostic technologies are concentrated in urban areas. Expanding portable imaging and tele-diagnostic services could bridge this gap.

• Specialized Pediatric Care: Few facilities offer pediatric subspecialties beyond general care, signaling a need for targeted development.

• National-Level Rehabilitation and Palliative Care: Services are fragmented and insufficient to meet population needs or support the growth of medical tourism.

Summary of Key Findings and Trends

Georgia’s healthcare sector is undergoing a transformative shift, driven by a decade of private sector expansion, increasing specialization, and gradual integration of digital health technologies. The system is evolving toward a dual-market model: on one side, high-volume, low-margin universal health coverage (UHC) services for the domestic population; on the other, high-margin, specialty-focused services catering to affluent local patients and international medical tourists.

Current market trends highlight the growth of private hospitals and diagnostic centers, rising interest in oncology, cardiology, fertility, and rehabilitation services, and accelerating momentum in telemedicine and AI-powered diagnostics. While medical tourism remains in its early stages, Georgia’s competitive pricing, liberal reproductive health legislation, and improving clinical infrastructure position it as a promising destination.

Nonetheless, several challenges persist. These include regulatory inconsistencies, shortages in key medical specialties, limited adoption of international accreditation standards, and the absence of a unified medical tourism brand. Financing structures remain skewed, with out-of-pocket payments accounting for over 50% of total health expenditure – posing a significant barrier to equitable access.

Core Recommendations

For Government

1. Regulatory Streamlining & EU Alignment

Develop a centralized licensing platform and align clinical and accreditation standards with EU directives. This will enhance investor confidence and support Georgia’s integration into the broader European healthcare ecosystem.

2. Targeted Workforce Development

Expand medical education capacity in critical shortage areas—such as oncology, rehabilitation, and anesthesiology—and implement bonded scholarship programs to retain skilled professionals within the country.

For Private Investors

1. Specialty-Driven Investment

Target high-demand, high-margin specialties—such as oncology, cardiology, fertility, and rehabilitation—capitalizing on Georgia’s strategic location to attract inbound medical tourists from neighboring regions.

2. Cluster Development

Cluster Development Establish integrated medical tourism hubs near airports and resort destinations to foster synergies between healthcare, wellness, and hospitality, creating a seamless experience for international patients.

1. Digital Health Integration

Implement interoperable digital platforms and AI-powered diagnostic tools to boost operational efficiency, enhance patient engagement, and ensure readiness for cross-border healthcare delivery.

For Healthcare Providers

1. Quality Systems as a Market Differentiator

Attain international accreditation and embed continuous quality improvement practices to enhance clinical standards and foster patient trust.

2. Service Diversification

Maintain a balanced portfolio by delivering high-volume services under universal health coverage (UHC) while offering premium care options tailored to private-pay patients and medical tourists.

3. Patient-Centric Branding

Implement coordinated marketing strategies that highlight transparency, clinical outcomes, and personalized care experiences to appeal to both domestic and international audiences.

Limitations and Future Research Areas

This study is constrained by gaps in publicly available data – particularly within the medical tourism segment—and by the lack of comprehensive integration between private and public health statistics. While expert interviews provided valuable qualitative insights, expanding the sample size could further strengthen the accuracy of projections.

Future research should prioritize:

• Conducting detailed cost–benefit analyses of proposed medical tourism clusters.

• Assessing the impact of AI and digital health adoption on patient outcomes and system efficiency.

• Undertaking longitudinal studies to evaluate the effects of EU alignment on healthcare investment flows.

Conclusion

Georgia’s healthcare sector is at a strategic inflection point. With targeted regulatory reforms, specialty-driven investment, and alignment with EU health standards, the country has the potential to emerge as a regional hub for advanced care and medical tourism. Realizing this vision will require coordinated efforts from government, private investors, and healthcare providers – ensuring that economic growth translates into equitable, high-quality healthcare services for all.

References:

• Akhvlediani T., & Khubua, G. (2021). Medical Tourism as a Driver for Healthcare Sector Development in Georgia. Tbilisi: Georgian Healthcare Management Association.

• Bennett S., Frenk J., & Mills A. (2018). The Evolution of the Health System Strengthening Agenda in low-income and Middle-income Countries. The Lancet, 392(10156), 1381–1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31351-8

• European Commission. (2023). EU–Georgia Association Agreement: Health Sector Alignment Roadmap. Brussels: European Commission Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety.

• Gotsadze G., Chikovani I., Sulaberidze L., & Goguadze K. (2019). Health Financing Policy in Georgia: Achievements and Challenges. Health Policy and Planning, 34(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czy126

• Joint Commission International. (2024). Accredited Organizations List. Retrieved from https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/

• Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Labour, Health and Social Affairs of Georgia. (2024). Healthcare Statistics Yearbook 2023. Tbilisi: MoH.

• National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2024). Statistical Yearbook of Georgia 2023. Retrieved from https://www.geostat.ge/en

• Porter M. E. (2008). The Five Competitive Forces that Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review, 86(1), 78–93.

• Temos International. (2024). Accreditation Standards and Certified Facilities. Retrieved from https://www.temos-international.com/

• World Bank. (2023). Georgia: Health Sector Policy Note. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

• World Health Organization. (2022). Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and their Measurement Strategies. Geneva: WHO Press.

• World Tourism Organization. (2023). Medical and wellness Tourism: Global Trends and Opportunities. Madrid: UNWTO.

• Zoidze A., & Gotsadze, G. (2020). Universal Health Coverage in Georgia: Policy Reforms and Future Directions. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4904-4

• Belli P., Gotsadze G. and Shahriari H. (2004). "Out-of-Pocket and Informal Payments in the Health Sector: Evidence from Georgia." Health Policy 70 (1): 109–123. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15312713/

• Gotsadze G., Chikovani I., Goguadze K. and Balabanova D. (2010). "Health Care-Seeking Behavior and Out-of-Pocket Expenditures in Tbilisi, Georgia." Health Policy and Planning 25 (3): 279–290. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15965035/

• Murauskiene L., Janoniene R., Veniute M., Ginneken E. and Karanikolos M. (2013). Lithuania: Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition 15 (2): 1–150. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/lithuania-health-system-review-2013

• Anneli K., Kahur K., Habicht J., Saar P., Habicht T. and Ginneken E. (2008). Estonia: Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition 10 (1): 1–230. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/estonia-health-system-review-2008

• Migle T., Vaskis J. and Stumbrys G. (2004). Latvia: Health Care Systems in Transition. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. https://www.idos-research.de/uploads/media/Studies_7.pdf

• Kangas O. (2010). "Finland: Between Delegation and Accountability." In Governance and Health Care in the Nordic Countries, edited by Jon Magnussen et al., 161–185. London: Open University Press.

• Esping-Andersen G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://lanekenworthy.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/reading-espingandersen1990pp9to78.pdf

• OECD. 2023. Health at a Glance: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-2023_7a7afb35-en.html

• European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. (2024). Denmark: Health System Summary. Health Systems in Transition. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/denmark-health-system-summary-2024

• Saltman Richard B. and Figueras J. (1997). European Health Care Reform: Analysis of Current Strategies. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/107267

• Bernd R., McKee M. and Healy J. eds. (2009). Health Systems in Transition: Template for Analysis. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/health-systems-in-transition-template-for-analysis

• Maarse H. and Paulus A. (2003). "Market Competition in European Health Care Systems: A Comparative Analysis." Health Policy 66 (2): 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8510(03)00046-5

• Stepurko T., Rachel B., Tambor M. and Brenna E. (2015). "Comparing Public and Private Providers: a Scoping Review of Hospital Services in Europe." European Journal of Public Health 25 (suppl_1): 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv060

• Georgian National Tourism Administration. Report on Medical Tourism, 2023. https://gnta.ge/statistics/

• BM.GE. Financial Review of the Georgian Healthcare Sector, (2021–2024). https://bm.ge/ka/news?category=healthcare

• Curatio International Foundation. Georgian Healthcare Sector Research, (2022). https://curatiofoundation.org/ka/publications/

• Produce in Georgia. Sectoral Review on Healthcare, 2023. https://www.enterprisegeorgia.gov.ge/ka/publications