Referential and Reviewed International Scientific-Analytical Journal of Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Faculty of Economics and Business

The Importance of Economic Analysis of Environmental Impacts: Theoretical Framework and Practical Policy Implications

It s been a subject of long-time discussions if environmental impacts matter as much as economic and social challenges facing the world today. One of the main causes why it is hard, not only for the general society but also for the professionals too, to have a clear picture of environment and climate-related challenges, is that these impacts are rarely analyzed in economic terms. The purpose of this study is to present the importance of economic analysis of environmental impacts and outline their role in modern welfare states. The paper uses comprehensive secondary data sources, quantitative and qualitative data analysis for this study; books, scientific articles, methodologies and guides as well as international organizations’ data and assessments are examined here.

Literature review method is used in the article to present the theoretical framework in detail. In particular, the importance of assessing environmental impacts is shown in connection with welfare economics, and the core economic concepts and models established in this field are reviewed. Concepts of utility, efficiency and cost-benefit analysis are briefly analyzed. The natural and environmental resources, as resources of “common-pool” and “public goods” are shown and total economic value methods are discussed there as the main applied techniques of economic valuation of non-market, including environmental impacts.

The part of results and discussions of the study is broken down into three main directions: (1) economic losses of environmental degradation and the environmental challenges facing the world today are examined in the research; (2) consideration of environmental components in impact assessment practice of high-income economies are presented in the study; (3) recent developments in numbers of international indices and national wellbeing models are presented in the study to show how environmental components are reflected in selected welfare indicators.

The article finalizes with the conclusions reflecting the main contributions of the study and proposing the areas of future researches in the field of economic analysis and valuation of environmental impacts.

Keywords: Environmental Impacts, Environmental Protection, Impact Assessment, Regulatory Impact Assessment, Cost-Benefit Analysis, Total Economic Value, Wellbeing, Welfare Economics

JEL Codes: P28, P48, Q50, Q51, Q56

Introduction

The development of policy making and impact assessment practices in the 21st century shows that modern welfare state is largely determined not only by social and economic aspects, but also by environmental categories. Environmental impacts take special role among non-market impacts, especially in light of the current global challenges, as well as within the framework of the sustainable development agenda of the world. These impacts are often neglected due to the difficulty of assigning them an economic value. Although, it should be taken into consideration that today's ecological challenges are important not only from environmental and social points of view, but also directly from an economic perspective – "it's not just about biodiversity, it's about the whole economy" (Taylor, 2021).

Current trends and general statistics regarding environmental protection and economic losses of ecological degradation worldwide shows the importance of economic analysis in environment and climate related issues. And these issues are important to incorporate in general policy making and impact assessment practices as well as in international and national indices measuring wellbeing of societies. Economic valuation of environment and its application is important not only to facilitate the evidence-based decision-making process, but also to raise public awareness. Through economic analysis, the essence of the issue becomes more visible to the general public, citizens and businesses, and this is expected to result in corresponding behavior changes, having positive impact on general well-being.

Economic valuation of impacts is related to the concepts of welfare economics, efficiency and utility as well as cost-benefit analysis and total economic value. In advanced nations the development of these fields began actively in the 19th century with various economic theories, and since the 20th century, practical implication has happened in public policies and projects.

The models for evaluating the economic value of impacts (and especially non-market impacts, including environmental ones) are constantly evolving today. The role and importance of assessing and valuing environmental impacts (as one of the key aspects of sustainable development) is increasing in such models. In order to support effective and efficient policy-making, important decisions about the projects of high public interest should be based on similar evidence-based studies and assessments.

Methodology

The presented research uses comprehensive secondary data sources, quantitative and qualitative data analysis for this study. Books, scientific articles, methodologies and guides as well as international organizations’ assessments were examined. Quantitative data was explored and assessed respectively – statistical data was collected through various sources, reports and articles. Rough data for analyzing impact assessment practice in economies of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and European Union (EU) was collected from the statistics produced within Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance by OECD. Databases and evaluations of international organizations and several international indices are used in the study.

In order to assess how economic analysis is used in policy making and observe if environmental impacts are taken into account in these processes, results of impact assessment (IA) practice, known also as regulatory impact assessment (RIA) is presented in this study. RIA is a systematic framework and a type of evidence-based techniques which is conducted in a way (a) to analyze the regulatory and non-regulatory alternatives for solving the problem under consideration, (b) to assess the impacts in terms of the positive and negative sides (costs and benefits) and (c) to choose the best policy option based on this analysis. There are three main reasons for choosing RIA practices for this study:

- RIA is a form of economic analysis of laws/regulations and the methodological basis of almost all RIAs is cost-benefit analysis (CBA) and its alternative forms, like cost-efficiency analysis (CEA), multi-criteria analysis (MCA) and other similar economic methods (UK HM Treasury, 2022), (EC, 2021), (NSW Government, 2017), (NZ Government, 2015), (EC, 2009), (OMB, 2003).

- Almost all RIA guides require assessing the impacts in different perspectives: direct and indirect impacts, short and long-term impacts, distributional impacts as well as impacts on major development areas – economic, social and environment (EC, 2021), (EC, 2009), (Ministry of Justice of Finland, 2008). In advanced economies there is practice of high-quality economic valuation of environmental impacts (UK HM Treasury, 2022).

RIAs are part of welfare state analysis. High-quality impact assessment practices ensure that public perceptions and attitudes are taken into consideration into policy making and diverse groups of stakeholders, individuals and businesses, participate in the processes (moreover, stakeholder participation is the central core element of RIAs). As mentioned above, RIAs usually require to assess the wide range of impact areas (economic, social, environmental), analyze impact on different target groups (government, citizens, businesses, vulnerable groups etc.), observe direct and indirect, medium and long-term effects of the policy/intervention. So, different perspectives of policies need to be considered in this process. In this way RIAs become a powerful tool to achieve sustainable development goals worldwide.

The analysis of RIA practice in this study is based on the OECD Dataset on the Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG) (OECD, 2022). Data are presented for 38 OECD member states, also another five non-OECD European countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Malta, Romania). In total, data for 44 economies (13 non-European OECD countries, 30 European countries plus EU itself) are presented in the examined indicators’ dataset. The selected indicators are analyzed below to capture the tendencies and practices that these economies have in terms of economic analysis (cost-benefit analysis and monetization of impacts) in policy making and in terms of inclusion of environmental impacts in policy analysis.

In addition to the RIA practices with regard to economic analysis and inclusion of environmental impacts, this paper studied several international indices that are designed in a way to assess the success, happiness and welfare of the countries in general or specifically for some selected categories. The article presents examples of international and national indices which incorporate environment-related components and shows if ecological aspects matter in such global well-being indicators.

Literature Review

Utility, Efficiency, Welfare Economics and Cost-Benefit Analysis

Throughout the history of society, well-being has been the subject of philosophical, sociological and broader scientific thought. After the early development of economics, the concept of well-being has been implicitly and clearly expressed through utility theories. Famous representatives of these theories were the English philosophers Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806 – 1873). They are known as "consequentialists". "Consequentialists" believed that whether a particular action is good or bad depends on its consequences. And the definition of “good” and “bad” should be judged strictly by the pleasure or pain, or both, that these actions cause. Despite the fact that there are different understandings of utilitarianism, its basic idea is the same for all and it is to maximize utility. Bentham described utility as the possession of something that produces positive effects or avoids negative ones. He called the attempt to value the full consequences of pleasure and pain the "Felicific Calculus". We can say that this is the same as the "welfare analysis", which is expressed by the total "social surplus" (sum of "producer surplus" and "consumer surplus"). Welfare economists strive to maximize the mentioned "social surplus". For utilitarians, everyone's happiness is considered to be of equal importance. Furthermore, when it comes to making specific social, economic or political decisions, utilitarian philosophy aims to improve the condition of society as a whole. According to utilitarianism, "it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong". This is roughly the idea behind modern welfare economics. So, 19th century utilitarianism can be considered the intellectual basis of what we now know as welfare economics or cost-benefit analysis (CBA).

The economic basis of CBA was further developed by Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923), Italian economist and sociologist. From Pareto's work comes the concept of "Pareto improvement", which occurs when at least one person's condition improves and no other person's condition worsens as a result of the distribution of resources in the economy. The second term "Pareto efficiency" refers to the situation where "Pareto improvement" is no longer possible. In practice, such “Pareto efficiency” is almost impossible, since all policy decisions result in “winners” and “losers”. A more pragmatic substitute for the Pareto criterion turned out to be the so-called "Potential Pareto" or "Kaldor-Hicks" (K-H) criterion, developed by English economists Nicholas Kaldor (1908-1986) and Sir John Richards Hicks (1904-1989). The main idea of K-H criterion is that economic efficiency is achieved and the policy/project is considered acceptable if the benefits received by the "winners" exceed the costs incurred by the "losers", since there will potentially be the possibility of transfer between these two parties and the Pareto criterion will be satisfied. In this way, using “net benefit” as a measure of efficiency separated efficiency and distributional effects, leaving the latter a matter for politicians and non-economists to judge. Thus, as suggested by Kaldor and Hicks, decision-makers should decide ethical issues related to equity beyond cost-benefit analysis. CBA has been developing in economic theory since then. For example, advances in methods for valuing non-market impacts have greatly expanded economic analysis in CBA. Although the K-H criterion is considered the standard of modern CBA even today, the agreement to solve fairness and efficiency as separate issues is changing and its truth is being questioned (Zebre, Davis, Garland, & Scott, 2013). What will be morally right, what is fair today and will be in the future, what will be administratively possible, etc. – such issues are increasingly taken attention to (Pearce, Atkinson, & Mourato, 2006).

The Concept of Total Economic Value and Economic Valuation of Non-Market Environmental Impacts

Both non-renewable and renewable natural resources are "common-pool resources" in the economic sense. Accordingly, they can be private, public or state property. Access to them is often not limited, but competitive. Examples of such resources are pastures, mineral resources, forests, etc. Since these resources are material in nature, they have a market value, although market values do not always reflect their true value to society. Environmental resources are what society enjoys, but it is difficult, if not impossible, to own them and economists call them "public goods". Examples of these goods are clean air, beautiful landscapes, the presence of rivers and plants, etc. In this case the resources are non-competitive and fully available to all (non-excludable). In economics, "biological resources" (comprising of both non-renewable and renewable natural resources, as well as environmental resources) is important to society in terms of the value of its potential use, i.e. from a "utilitarian" point of view. Attaching monetary value to such non-market environmental impacts is a challenging and sometimes impossible work.

Economic valuation is part of the economic analysis and it gives important results about the values of impacts in general, including environmental impacts. The market often does not set a specific price for a number of social and environmental aspects, although their importance is expressed in a different direct or indirect way in the lives of individuals and society as a whole. That’s why it is important to use techniques, such as total economic value (TEV) for analyzing and valuing these impacts. The purpose of economic value assessment techniques is to reveal the TEV of the studied product/effect. The total economic value is divided into use value and non-use value (Pagiola, Von Ritter, & Bishop, 2004) (Ozdemiroglu, et al., 2006), (Clough & Bealing, 2018). Use value includes the use of a specific resource (product and/or service), directly or indirectly, for example: (a) fishing and hunting are direct uses; (b) flood retention ponds are examples of indirect use. Another category of use value is called “option value” – example of that would be when people take care of forest resources for the hiking possibilities in the future. Non-use value is related to the care that comes from knowing that the natural environment is being preserved and includes mostly spiritual, cultural values, "sense of belonging". Non-use value includes such components as (a) existence value: satisfaction of knowing about the future existence of a specific resource (animals, birds, mountains, landscapes, etc.); (b) bequest value: knowledge that the environment's resources will be passed on to future generations; (c) altruistic value: desire to have a healthy environment for all living organisms now and in the future.

In international practice, several basic methods for estimating the total economic value of non-market impacts (including environmental effects) are known (UK HM Treasury, 2022), (ELD, 2019): (i) market-based methods, which are used if estimations can be made by observing market prices – hedonic pricing is an example of this method; (ii) non-market methods can be used in the form of revealed preference methods and stated preference methods. The above-mentioned "use-value" can be evaluated by both revealed and stated preference methods. However, the assessment of "non-use value" is done only by the stated preference method; (iii) subjective well-being methods – this approach aims to reflect the direct impact of politics on well-being. Methodology on the application, measurement and evaluation of well-being concepts is developing and may be particularly useful in certain policy areas, like societies and environmental protection.

Results and Discussion Economic Losses of Environmental Degradation

A number of studies and assessments indicate the economic losses caused by environmental damage. 51 countries of the world will lose 10-20% of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP) only at the end of this decade in case of an ecosystem crisis (Taylor, 2021). Back in 2008, the global economy lost 2-5 trillion US dollars due to deforestation (Goodwin, 2008). In the same period, the total cost of environmental degradation in the countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) was estimated at an average of 5.7% of GDP (Hussein, 2008). According to more recent studies, for example, the cost of ecological degradation in Morocco reaches 3.5% of GDP (Croitoru & Sarraf, 2018) and in Indonesia it reaches 13% of GDP (Pirmana, Alisjahbana, Yusuf, Hoekstra, & Tukker, 2021). According to the European Environmental Agency (EEA, 2022), between 1980 and 2020, economic losses equal to 487 billion Euros were recorded in the 27 member states of the EU due to climate-related events. According to Eurostat, in the same 27 member states of EU, heat, floods and hurricanes caused economic losses of 145 billion Euros during the last decade (Ellerbeck, 2022). Environmental pollution is directly related to the deterioration of human health and well-being (WHO, 2023), (Brink, et al., 2016) which is also a cost for society and economy, in general.

According to latest survey of Environmental Performance Index (EPI) (Wolf, Emerson, Esty, Sherbinin, & Wendling, 2022), deteriorating air quality and rapidly rising greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions pose especially urgent challenges for the world. Besides, the latest results of Ecological Footprints (EF) data (GFN, 2022) shows that only 28% of the world's countries have biological/ecological reserve, while all other countries are in ecological/biological deficit.

A well-known model depicting the connection between environmental protection and the economy is the so-called "Environmental Kuznets Curve” (EKC). According to EKC, along with economic growth, the environmental situation worsens in countries, however, in already rich countries, the environmental situation changes for the better. Practice shows that this is not always the case (Wang & Lu, 2019). Environmental pollution causes significant social health costs and prevents sustainable economic development and social well-being. Therefore, it is necessary to integrate ecological goals into the economy despite the level of the country’s development. It is also important to note that developed and high economy countries stand out with the best results in the above-mentioned EPI indicator, while the EF index does not confirm this positive relation between the variables, as the highest "ecological/biological reserve" is depicted in numbers of poor countries, in contrast to developed and economically strong countries.

Environmental Components in Impact Assessment Practice

According to the data collected within the Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance project (World Bank, 2018), 47% of all surveyed countries (186 world economies) conduct regulatory impact assessment (RIA) worldwide. High-income OECD countries are global leaders in terms of conducting RIAs and communicate them to the public. RIA adoption in OECD countries have been particularly rapid since 1974 with the highest growth observed during 1994-2002 (OECD, 2009). According to latest 2021 data (OECD, 2022), almost all of OECD countries and all European OECD countries have requirements to conduct RIA and implement RIA works in practice to inform the development of primary and/or secondary legislations. Although, it should be mentioned that covid-19 pandemic crisis had affected impact assessment system globally and the “avoidance” of RIAs even during crisis is not considered positively (OECD, 2020), (Bancroft, 2020), (Mota , et al., 2020). In 2021, compared to 2017, the number of countries which made exceptions to the need to conduct RIA on emergency laws and regulations increased from 12 to 16 for primary laws and from 13 to 18 for subordinate regulations (OECD, 2021). It is important to “recover” impact assessment practice and support ex-ante analysis as well as ex-post evaluations to restore confidence in regulatory decisions (OECD, 2020).

As mentioned above, almost all of OECD countries and all European countries have requirements for RIA and practically conduct RIAs (OECD, 2022). In addition, all survey participant countries have declared that by 2021 they provide written guidelines on the preparation of RIA. What about guidance’s on cost-benefit analysis and giving advices on monetization of costs and benefits in RIA guidelines, absolute majority (80-90%) of EU and all OECD countries declare that they have such practices. As the results show, assessing costs is more prevalent within surveyed countries, than assessing benefits of regulations. Besides, both costs and benefits of regulations are assessed by a little more countries in case of subordinate regulations, compared to primary laws. This picture is reverse in EU countries – costs and benefits of regulations are assessed by more economies in case of primary laws, compared to subordinate regulations. One of the most significant results that this survey shows, is about the rule of decisions in RIA, i.e. the study asks if there is a formal requirement for regulators to demonstrate that the benefits of regulations justify the costs. As we know, RIA is methodologically based on CBA and other similar techniques and it means that the best alternative (policy option) should be chosen by their net positive benefits, i.e. when benefits justify the costs and the higher the indicator, the better the alternative is. Although, the role of qualitative analysis should not be underestimated here – some impacts (not presented as quantified and monetized costs and benefits) can be presented in non-monetary terms in the analysis and the decision can be made by combining both valued and non-valued impacts. As the results show, 61% of OECD countries stated that they never have this requirement (to demonstrate that the benefits of regulations justify the costs) in case of both primary laws and subordinate regulations. In EU this indicator is even more – according to 74% and 77% of surveyed EU economies, they never have such requirement in case of primary laws and subordinate regulations, respectively.

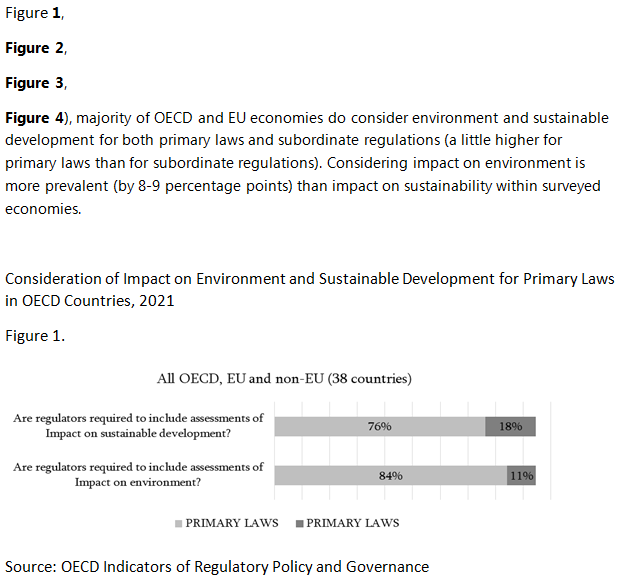

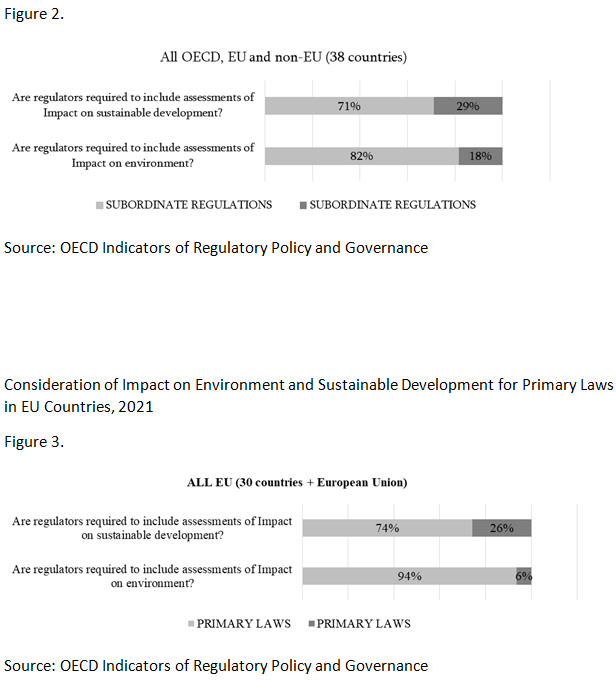

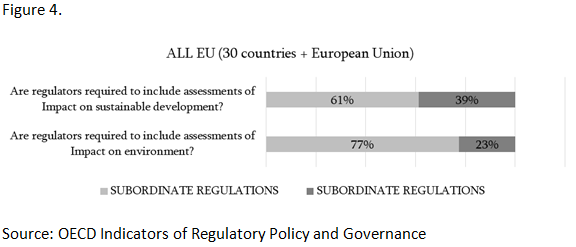

Surveyed economies were asked if they consider impact on environment and sustainable development in their impact assessment practice. As the results show

Consideration of Impact on Environment and Sustainable Development

for Subordinate Regulations in OECD Countries, 2021

Consideration of Impact on Environment and Sustainable Development for Subordinate Regulations in EU Countries, 2021

Worth mentioning the fact that, in case of primary laws, 29% of OECD countries and 39% of EU economies reported to never having a requirement for assessing risks for environmental regulations. In case of subordinate regulations, these numbers reach 37% for OECD and 45% for EU economies.

Environmental Components in Selected Welfare Indicators

It is difficult to agree on a common definition of happiness or well-being that is acceptable to everyone, however, the world's ongoing challenges make it clear that it is not determined by only economic factors, neither at the level of an individual nor at the level of the country as a whole – “There is more to life than the cold numbers of GDP and economic statistics“ (OECD, 2015). Today countries agree that the balance of social, environmental and economic aspects is the main principle of sustainable development.

Several international and national models and indices, measuring the general level of human development and well-being in countries, already integrate environmental components in their assessments. OECD periodically publishes “OECD Well-being Dashboard“, i.e., the data about “How's Life? Well-Being” and “Better Life Index“ (OECD, 2022). This dashboard measures various categories of the quality of human life and living, including health and safety of the living places, environmental quality and subjective well-being. Human Development Index (HDI) classically measures countries' achievements in three areas: (1) long and healthy life, (2) literacy/literacy, and (3) a decent level of life, and economic income. An ecological component has recently been added to this assessment (UNDP, 2022) and now the index is adjusted according to the indicators of damage caused to the planet (greenhouse gas emissions, "ecological footprint"). Additionally, some specific economic and finance indicators began to incorporate environmental components and/or have been adjusted to consider climate and ecological issues within them. For instance, Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) measures the success of countries in terms of (a) enabling environment, (b) human capital, (c) markets, and (d) innovation. For the first time in 2019 such components as "energy efficiency regulations", "renewable energy regulations" and "implementation of agreements related to environmental protection~ appeared in GCI (Schwab, 2019). Another example is Public Investment Management Assessment (PIMA) framework by International Monetary Fund (IMF). PIMA has recently been updated to Climate-PIMA to assesses countries’ capacities and their practices in using climate perspectives for managing public capital infrastructure projects (IMF, 2023).

In addition to the changes observed in international assessments and indices, approaches are also changing at the national/countries level and environmental impacts are gaining more importance. For example, selected components of environmental stance (air quality and GHG emissions) are among the determinants of national welfare indicators of Australia (AIHW, 2021). In addition, the United Kingdom's Office for National Statistics publishes the National Well-Being Dashboard (ONS UK, 2022), according to which well-being is assessed in ten areas, such as: Personal wellbeing, Health, Relationships, Environment, “What we do”, “Where we live”, Personal finances, Governance, Economy, Education and skills. It is important that these assessments include both objective (actual statistical data produced in various aspects/fields) and subjective data (household surveys for assessing individual attitudes etc.). The development of similar models in the country itself requires the practical implementation and steady development of the above-described economic valuation methods of non-market (including environmental) impacts.

Conclusion

The paper presented the essence of economic analysis in policy making, the need for economic valuation of environmental impacts, their importance and their connection with the well-being of societies. The discussed topics are presented from both scientific and practical points of view.

The study reviewed the literature and theoretical framework of the subject under this article. A brief theoretical examination analyzed the development of relevant economic theories and concepts from utilitarianism and “consequentialism“ to “pareto efficiency“ and modern K-H criterion of cost-benefit analysis. This part discussed the foundations of welfare economics in general and the concept of total economic value in particular, the case of natural and environmental resources as "common-pool resources" and "public goods" and the methods related to their valuation. Economic analysis (valuation) of environmental impacts, even among economists, is associated with significant challenges, since the market price for environmental and natural resources is often not determined, and it becomes necessary to conduct important and complex studies through various market and non-market based methods, like “hedonic pricing”, "revealed preference" and "stated preference" methods and other similar techniques.

The results of the study are discussed in three directions in the paper:

- Economic losses of environmental degradation – as the results of the research show, the ecological challenges facing the world today are important not only from the environmental protection and social point of view, but also directly from the economic perspective. Practice shows that the EKC does not always work even in already developed, high-income countries, and, therefore, it is necessary to integrate ecological components into the country's development processes, regardless the economic situation. The damage that the world receives as a result of ecological degradation is significantly high and increasing. According to several international assessments (including EPI, EF), the world needs urgent actions for the environmental challenges facing the planet today.

- Environmental components in impact assessment practice – Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance by OECD were thoroughly analyzed for OECD and EU economies. The results show that absolute majority of high-income economies do have RIA practices established in their jurisdictions, they consider costs and benefits, including environment and sustainable development impacts of the policy options while developing primary laws and secondary regulations. Some issues here need to be taken attention and considered in the future research directions. For example, the data shows that the CBA and RIA decision rule (rule of “net benefit” – demonstrate that the benefits of regulations justify the costs) are not always required in practice. For future research it will be important to assess what these results imply in reality – does it mean that analyzing costs and benefits of policy options is formal procedure or it just means that several non-market impacts (which are not quantified and monetized and are usually qualitatively assessed) are not included in this “net benefit” criteria and that’s why the strict CBA rule does not apply there.

- Environmental components in selected welfare indicators – practice shows that numbers of international indices (like HDI, GCI, PIMI etc.) and national well-being models recently started to integrate environmental components in their assessments. There is a tendency of environmental and green economics growing in parallel with the sustainable development agenda in the world, and as part of this, countries reflect environment and climate related issues in their national priorities and policy making processes. This, in turn, requires the advancement of the field and the practical application of non-market environmental impact valuation models.

Finally, it should be noted that an economic view of environmental impacts can change public attitudes towards this area. It is often heard not only from the society as a whole, but also from the professional circles that issues of economic and social development are higher priorities than the protection of the environment. This opinion can only be based on preconceptions and pre-defined attitudes, since the results of a thorough and economic analysis of the field give us the clear picture: the low priority of environmental issues, in the light of today's challenges, may lead to the aggravation of social and economic problems and the impoverishment of the poor population, vulnerable groups "being left behind". Analysis of available statistical data reveals that environmental damage has a direct impact on human physical and mental health and quality of life in general. Without the economic analysis of environment and climate change issues, these fields have a tendency to remain of low priority and secondary importance. Hence, contributing scientific development of this field and practical application of the economic valuation methods of environmental impacts are of high significance for scientists, professionals, policy makers and the public in general.

References:

- AIHW. (2021). Australia’s Welfare Indicators. Retrieved 2023. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW): https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/indicators/australias-welfare-indicators

- Bancroft D. (2020, June 30). Curtailing Work on Impact Assessments due to covid-19 is Unjustified. Retrieved December 27, 2021.https://www.iaia.org/news-details.php?ID=123

- Brink P. T., Mutafoglu K., Schweitzer J.-P., Kettunen M., Twigger-Ross C., Kuipers Y., Ojala A. (2016). The Health and Social Benefits of Nature and Biodiversity Protection – Executive Summary. European Commission, Institute for European Environmental Policy. Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP). Retrieved December 28, 2022 https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/biodiversity/intro/docs/Health%20and%20Social%20Benefits%20of%20Nature%20%20Final%20Report%20Executive%20Summary%20sent.pdf

- Clough P., & Bealing M. (2018). What’s the Use of non-Use values? Non-Use Values and the Investment Statement. New Zealand Institute of Economic Research. NZ Institute of Economic Research (Inc). Retrieved December 27, 2022. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2018-08/LSF-whats-the-use-of-non-use-values.pdf

- Croitoru L., & Sarraf, M. (2018). How Much Does Environmental Degradation Cost? The Case of Morocco. Journal of Environmental Protection. Retrieved December 28, 2022. https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation.aspx?paperid=83364

- EC. (2009). Impact Assessment Guidelines. European Commission (EC). Retrieved July 30, 2022.https://ec.europa.eu/smartregulation/impact/commission_guidelines/docs/iag_2009_en.pdf

- EC. (2021). Better Regulation Guidelines. European Commission (EC). Retrieved July 30, 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-making-process/planning-and-proposing-law/better-regulation-why-and-how/better-regulation-guidelines-and-toolbox_en

- EEA. (2022, February 3). Economic losses from Cimate-Related Extremes in Europe. Retrieved December 28, 2022. https://www.eea.europa.eu/ims/economic-losses-from-climate-related

- ELD. (2019). Valuation of Ecosystem Services. The Economics of Land Degradation (ELD). ELD Initiative. Retrieved December 27, 2022. https://www.eld-initiative.org/en/knowledge-hub/eld-campus/

- Ellerbeck S. (2022, December 2). Climate change has cost the EU €145 billion in a decade. World Economic Forum. Retrieved December 28, 2022. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/12/climate-europe-gdp-emissions/

- GFN. (2022). Explore the data / Ecological Footprint. Retrieved December 2022, from Global Footprint Network (GFN): https://data.footprintnetwork.org/?_ga=2.78000156.943753268.1673871607-686570692.1673871603#/

- Goodwin J. (2008, October 28). The Economic Costs of Environmental Degradation. Center for Progressive Forum. Retrieved December 28, 2022. https://progressivereform.org/cpr-blog/the-economic-costs-of-environmental-degradation/

- Hussein M. A. (2008). Costs of Environmental Degradation: An Analysis in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Management of Environmental Quality. Retrieved December 28, 2022.https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/14777830810866437/full/html?skipTracking=true#:~:text=These%20long%2Dlasting%20challenges%20have,7.4%20per%20cent%20of%20GDP.

- IMF. (2023). Climate-PIMA (Public Investment Management Assessment). Retrieved 2023, Infrastructure Governance / International Monetary Fund (IMF): https://infrastructuregovern.imf.org/content/PIMA/Home/PimaTool/C-PIMA.html

- Ministry of Justice of Finland. (2008). Impact Assessment in Legislative Drafting / Guidelines. Ministry of Justice of Finland. Retrieved March 2023. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/76118/omju_2008_4.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Mota D. M., Saab F., Vazzoler R. Z., Schunig K., Donagema E. A. & Troncoso G. C. (2020, June 9). Regulatory Impact Assessment in Pandemic Times: a Practical Exercise in the COVID-19 Context. Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency. Revista Do Serviço Pwblico. doi:https://doi.org/10.21874/rsp.v71i0.4824

- NSW Government. (2017). Guide to Cost-Benefit Analysis. The Treasury of Australian Government, New South Wales (NSW) Government. Retrieved July 2022. https://www.treasury.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2017-03/TPP17 03%20NSW%20Government%20Guide%20to%20Cost-Benefit%20Analysis%20-%20pdf_0.pdf

- NZ Government. (2015). Guide to Social Cost Benefit Analysis. The Treasury of New Zealand (NZ) Government. Retrieved July 30, 2022. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2015-07/cba-guide-jul15.pdf

- OECD. (2009). Government at a Glance. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Retrieved March 2023, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264075061en.pdf?expires=1680259172&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=D94A1302D5D77C507AADDE0A0595BBCE

- OECD. (2015). OECD Better Life Index. Retrieved 2023, from Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD): https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/#/11111111111

- OECD. (2020, September 30). Regulatory Quality and COVID-19: The Use of Regulatory Management tools in a Time of Crisis. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Retrieved March 2023. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=136_136858-iv4xb9i639&title=Regulatory-quality-and-COVID-19-The-use-of-regulatory-management-tools-in-a-time-of-crisis

- OECD. (2020, July 27). When the Going Gets Tough, the Tough Get Going: How Economic Regulators Bolster the Resilience of Network Industries in Response to the COVID-19 Crisis. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Retrieved March 2023, from https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=135_135364-qc5jpyar8f&title=When-the-going-gets-tough-the-tough-get-going-how-economic-regulators-bolster-the-resilience-of-network-industries-in-response-to-the-COVID-19-crisis

- OECD. (2021). Government at a Glance. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Retrieved March 2023. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/1c258f55en.pdf?expires=1680263772&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=496BD4E69848556B191E9961AE4BA696

- OECD. (2022). Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance. Retrieved March 2023. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD): https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=GOV_REG

- OECD. (2022). Social Protection and Well-Being. (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)) Retrieved 2023. OECD Statistics: https://stats.oecd.org/

- OMB. (2003). Circular A-4 Regulatory Analysis. Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Retrieved July 30,2022. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/regulatory_matters_pdf/a-4.pdf

- ONS UK. (2022). Measures of National Well-being Dashboard. Retrieved 2022. Office for National Statistics of United Kingdom (ONS UK): https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/measuresofnationalwellbeingdashboard/2018-04-25

- Ozdemiroglu E., Tinch R., Johns H., Provins A., Powell J., & Twigger-Ross C. (2006). Valuing Our Natural Environment. Eftec in Association with Environmental Futures Limited, For Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Retrieved December 27, 2022. https://iwlearn.net/resolveuid/31143e1709af2d73752e773c6af552d9

- Pagiola S., Von Ritter K., & Bishop J. (2004). Assessing the Economic Value of Ecosystem Conservation. The World Bank in Collaboration with The Nature Conservancy and IUCN—The World Conservation Union, The World Bank Environment Department. The World Bank. Retrieved December 27, 2022. https://www.cbd.int/doc/external/worldbank/worldbank-es-value-02-en.pdf

- Pearce D., Atkinson G., & Mourato S. (2006). Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment – Recent Developments. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). OECD. doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264010055-en

- Pirmana V., Alisjahbana A. S., Yusuf A. A., Hoekstra R., & Tukker A. (2021). Environmental Costs Assessment for Improved Environmental-Economic Aaccount for Indonesia. Journal of Cleaner Production, 280. Retrieved December 28, 2022. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652620345650

- Schwab K. (2019). The Global Competitiveness Report. World Economic Forum. Retrieved 2023. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2019.pdf

- Taylor M. (2021). World Bank: Economy Faces Huge Losses if we Fail to Protect Nature. World Economic Forum. Retrieved December 28, 2022. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/07/climate-change-economic-cost-world-bank-environment/

- UK HM Treasury. (2022). The Green Book: Appraisal and Evaluation in Central Government. HM Treasury and Government Finance Function. Retrieved December 27, 2022.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-governent

- UNDP. (2022). Table 7: Planetary Pressures-Adjusted HDI. Retrieved 2022. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/documentation-and-downloads

- Wang L., & Lu J. (2019). Analysis of the Social Welfare Effect of Environmental Regulation Policy Based on a Market Structure Perspective and Consumer. Sustainability. Retrieved January 17, 2023. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/1/104

- WHO. (2023). Air Pollution Data Portal. Retrieved 2023. World Health Organization (WHO): https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/air-pollution?lang=en

- Wolf M., Emerson J., Esty D., Sherbinin A., & Wendling Z. (2022). www.epi.yale.edu. Retrieved 2022, from https://epi.yale.edu/

- World Bank. (2018). Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance. Retrieved March 2023. The World Bank: https://rulemaking.worldbank.org/en/data/comparedata/assessment

- Zebre R. O., Davis T. B., Garland N. & Scott T. (2013). Toward Principles and Standards for Benefit Cost Analysis. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.4337/9781782549062