Referential and Reviewed International Scientific-Analytical Journal of Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Faculty of Economics and Business

Accounting and Audit Reform in Georgia: Theoretical and Descriptive Analysis

This work was supported by Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation of Georgia (SRNSFG) [grant number: FR17_489, Project Title: Are Georgian Private Sector Entities Engaged inFinancial Information Manipulation?

Georgian government enacted the Law of Georgia on Accounting, Reporting and Auditing as of June 8, 2016. The law has required entities of first and second categories as well as Public Interest Entities (c.a. 600 entities) to report their financial statements latest on October 1st, 2018. Groups of the third and fourth categories (c.a. 83.000 entities) shall report their financial statements latest on October 1st, 2019. As the regulation towards massive transparency takes place for the first time in the country’s history, it is a unique possibility not only for data-seeking researchers (like us), but also for the regulators and standard-setters in Georgia and within the EU. Before the larger dataset enters the playing field by the end of this year and before grasping the roots of financial information quality provided within the financial statements, this research project aims to theoretically review the ongoing reform details, descriptively analyze the already available data of about 600 entities and draw the first estimations of the reform outcomes. Our analysis suggests that the ongoing reform positively differs from any of its predecessor attempts in several regards: the reform’s regulatory window is consistent with the EU framework/experience; the processes are actively (financially and administratively) supported by international organizations; an active focus is given to the increase of interested parties’ awareness and understanding of the accounting fundamentals; monitoring process is stronger and stricter. Findings show that the mandated legislation is well-obeyed; few entities have even voluntarily published their audited financial statements; a high proportion of the reports is audited by large audit firms. These details enable us to expect that the currently ongoing field reform, unlike to previous attempts, will lead to significantly different positive outcomes.

Keywords: Accounting and audit; Reform; Georgia; Accounting quality; Disclosure; Enforcement.

JEL Codes: M40, M42, M48

Introduction

Laws and standards are mostly established based on the experience of the developed world, while the under-developed countries merely mirror those regulations and their private sectors in some cases do not even bring enough professional skills to appropriately follow the dictated rules. Despite the ongoing globalization of financial flows and the increasing reach of transnational disclosure regulation, it remains unclear how underdeveloped markets are touched by these developments. In the absence of a theory on how flows and regulations spread, we are in need to consider countries on a case-by-case basis. Even given a (corroborated) theory, we might still need to consider cases as soon as the specific institutional basis within the underdeveloped markets warrants closer inspection (La Porta et al. 1998; Zimmermann and Werner 2013; Pirveli 2015). To serve up the existing research gap, this work will examine the first-hand reform outcomes of the accounting and audit field in the light of an under-developed economy of Georgia.

The field of accounting and audit in Georgia has been a subject of changes since the independence from the Soviet Union. The field, however, systematically experienced solid problems, related, among others, to the regulatory base’s deficiencies (e.g., unclear categorization of entities, particularly of PIEs), inefficient transparency of financial reports and accountants and auditors’ limited understanding of the accounting fundamentals (particularly related to accruals-based transactions), all together promoting to Georgian entities’ deficient access to finances (World Bank Group 2007, Georgian Government 2013, McGee 2014, Pirveli 2014, 2015).

In the framework of the signed Association Agreement between the EU and Georgia, the Law of Georgia on Accounting, Reporting and Auditing was enacted in 2016 (Law 2016). The law brought some marked changes to the field. Entities have been categorized into 4 classes according to their size, profitability and number of employees. Legal entities of the first and the second categories as well as Public Interest Entities (PIEs) had to report their financial, managerial and audit reports of the financial year 2017 not later than October 1st, 2018. Legal entities of the third and fourth categories shall report their consolidated financial statements of the financial year 2018 not later than October 1st, 2019 (Law 2016). This implies about 84.000 entities to become transparent by the end of this year. It is a unique possibility for academics, regulators in Georgia and within the EU, and standard-setters. Before this massive dataset breaks a transparency threshold, in this paper we aim to provide the first-hand assessment of the ongoing reform as well as estimations for the near future. To formulate pertinent estimations, we aim to compare the overall objective of the reform to its initial achievements. Before going deeper within financial statements and thus being able to assess the quality of the therein provided information, we base our analysis on a careful review of the reform-related steps, as well as on an already available descriptive information of about 600 legal entities of I and II categories and PIEs for which the annual financial statements are already publicly available by January 20, 2019 (the last date we have collected the data).

We note several aspects why the currently ongoing reform might be significantly different from any of its predecessor attempts. Theoretical review of the reform details has revealed few aspects how the current regulatory changes may differ from its predecessor attempts and thus may reflect into outstanding outcomes. First, the currently ongoing changes align with the EU framework; that is, the processes are governed, managed, administered and financially supported by foreign authoritative parties, which may already represent a crucial tool to achieve sundry results. The law of 2016 is also aligned with and based on the European framework and intensive debates/workshops are held to monitor and plan the steps of a Georgian regulatory body, Service for Accounting, Reporting and Auditing Supervision (SARAS). Second, the ongoing reform targets and fights, among others, against the weaknesses/deficiencies previously associated with the Georgian accounting and audit field. The law of 2016 has categorized entities in four different clusters plus the Public Interest Entities. Only in 2017, SARAS has enacted 10 normative acts, which, among others, covered Professional Certification and Continuous Education standards. In 2018 SARAS’s focus has shifted form the establishment of the regulatory base, towards the increase of the interested parties’ awareness. A particular attention has been paid to a professional translation process of the related materials and standards in the field. This has been mostly done through the establishment of different textbooks as well as conduction of trainings and informative meetings. Importantly, SARAS created and administered electronic web-site and portal for reporting financial and managerial statements.

Descriptive statistics reveal that almost all required entities (more than 90%) have submitted their reports of 2017. This in some cases required either warning or a sanction from SARAS. It is difficult to judge how timely entities have followed the requirements as SARAS itself played a mediator role and has published the reports publicly only after controlling the statements. Few noteworthy aspects are: almost half of the entities used the audit service of big 6 audit firms. This may indicate that large Georgian entities, presumably because of gaining the credibility from banks or other credit agencies, do not hesitate to use the costlier services of bigger audit firms (DeAngelo 1981; Francis et al. 1999; Francis 2004; Gvaramia 2014; Pirveli 2015).

The reform not only does improve the awareness of the involved parties, but also increases the overall transparency of the private sector’s financial health and improves legal entities’ adherence to the dictated rules. Consistent to these findings, we cautiously predict that the actively led accounting reform will bring unexperienced positive outcomes to the field. While we believe the reform will reflect into a better-quality financial information, the question remains: what time the reform would necessitate to bring the tangible and visible results to the playing field.

Theoretical Background

Prior Literature on Disclosure Regulation

There is a long-standing literature on disclosure regulation, covering scientific thoughts from accounting, finance, economics and law fields. Debates on the optimal regulation of disclosures typically intensify in the crisis aftermath periods (e.g. Sarbanes-Oxley Act after the accounting scandals at the outset of 21st century (Ge and McVay 2005, Li et al. 2006, Lobo and Zhou 2006, Zhang 2007, Cohen et al. 2008C:UsersstudentiDownloadsCohen, - _blank) or Basel III after global financial crisis of 2007-2008 (Blundell-Wignall and Atkinson 2010, Cosimano and Hakura 2011, Slovik and Cournède 2011C:UsersstudentiDownloadsSlovik, - _blank)). Disclosure regulation is important field of research as it sets out the legal window, defining the forms, intensity and details to be provided within the financial reports (Jensen and Meckling 1976, Myers and Majluf 1984C:UsersstudentiDownloadsMyers, - _blank).

Extant literature has assessed the consequent pros and cons of the disclosure regulation many times. Since 1981, most of the extant literature on disclosure regulation focused on information transfers at capital markets (Foster 1981, Merton 1987C:UsersstudentiDownloadsMerton, - _blank). The underlying theory on disclosure regulation traces back to the principle agent theory. Information asymmetries among financial information users lead to adverse selection at the capital markets. Less informed investors worry about trading against more informed investors and thus they decrease (increase) the price at which they are willing to buy (sell) to protect against the losses caused by their information disadvantage. This price protection leads to a bid-ask spread into secondary share markets. As such the existing information asymmetry and the consequent adverse selection reduce the number of shares that less informed investors are willing to trade, reducing the liquidity of capital markets. Efficient disclosure regulation, by leveling the playing field among traders, addresses the mentioned adverse selection problem and reflects into increased liquidity, lower cost of capital and increased firm value (Milgrom 1981, Leuz and Verrecchia 1999, Verrecchia 2001C:UsersstudentiDownloadsVerrecchia, - _blank). Without corporate disclosures, investors are unable to distinguish between good and bad firms and therefore offer a price that reflects the average value of all firms. Hence, firms with an above-average value have an incentive to disclose private information about their true value. Once these firms disclose, investors rationally infer that the average value of all non-disclosing firms is lower and adjust the price to reflect this expectation (Grossman and Hart 1980, 1980, Grossman 1981, Francis et al. 2008C:UsersstudentiDownloadsFrancis, - _blank).

The preceding discussion illustrates that mandatory disclosure can have a number of benefits and be socially desirable. However, disclosure regimes are also associated with costs. First, mandatory regimes are costly to design, implement and enforce (Stigler, 1971). The costs of corporate disclosures include direct costs of its preparation, auditing and dissemination as well as the opportunity costs. Reporting costs, due to economies of scale, might be a serious issue particularly for smaller entities. Public disclosure bears another dimension of costs which is the risk of the disclosed information to be used by competitors, regulators, tax authorities, and others. Revelation of the business strategies may cover proprietary details and negatively affect its disclosure incentives (Gal-Or 1987, Verrecchia 1990, Wagenhofer 1990, Feltham and Xie 1992C:UsersstudentiDownloadsFeltham, - _blank). In summary, there are numerous direct and indirect disclosure costs as well as benefits, which in turn are likely to make the optimal amount of disclosure specific to each firm (sector or industry).

A careful examination of the extant literature on disclosure regulation shows that this literature overwhelmingly focuses on: a) capital markets: by analyzing capital market effects (liquidity, cost of capital and firm value) and by assessing capital market listed firms as well as the relationships between investors and management, b) firm-level effects, which indirectly should imply the market-wide (country-level) effects as well and c) on developed economies: where capital markets are relatively more efficient and the consequent data for the listed firms are welcomingly available. In the context of Georgia, however, to examine the potential outcomes of the currently ongoing disclosure reform, we are in need to change our focus. This is because, capital market of Georgia is still in its incipient stage of development. Under these conditions, the lion's share of the functioning of the financial system comes to the banking sector. Market incentives cannot affect reporting choices. While so, the pressure on reporting choices transpose from capital markets towards the banks. According to previous literature, together with the banking sector, the impact of state and the consequent tax incentives (tax evasion) importantly drives the reporting choices. Moreover, the reform that is discussed in this paper touches to all four categories of the entities (plus PIEs), within which the micro, small and medium sized entities constitute the major bulk compared to the capital market listed entities. Finally, as we aim to assess the ongoing reform at a country level, we need to discern between firm- and country-level effects. That is, to address whether disclosure regulation would bring positive affects at a country level by attracting more foreign investments and thus promoting GDP growth (Daske, 2008, Biddle, 2009).

Historical Overview of Accounting and Audit Field in Georgia

Within the first years following independence from the Soviet Union, a chaos prevailed within the accounting and audit field in Georgia. No legislation existed to regulate the sector; accounting and auditing firms were established spontaneously, and staff in those companies experienced a solid lack of international practice (Kaciashvili 2003, Pirveli 2015). The Law on Auditing and the Law on the Regulation of Accounting and Financial Reporting were launched in 1995 and 1999, respectively (Law 1995, 1999). Establishment of the regulatory base – aimed to recognize the international financial reporting standards – was an important step along the policy-makers’ will to transform the country into a market-based, capitalist society. However, debates towards the quality of the regulatory base have been intensified over the following decades. The government, as well as the private sector confessed a necessity of considerable changes within the laws – e.g., a clearer classification of public interest entities’ status, increased public availability of financial statements, and more (World Bank Group 2007, McGee 2014, Alagardova and Manuilova 2015, Pirveli 2015).

The first assessment of the accounting and audit field in Georgia was done by the World Bank in 2007. World Bank report (2007) stated there was a need of considerable reforms in the field, and provided the consequent policy-relevant recommendations. The field needed: a) an increased transparency and reach to entities’ disclosures, b) a clearer definition of Public Interest Entities’ status, c) entities’ categorization by size and the consequent allocation of reporting requirements due to each category, d) establishment of audit registry and f) higher attention and resources dedicated to professional trainings as well as materials’ translation and g) stricter enforcement of the law.

Accounting and audit laws were unified for the next draft version, signed in June, 2012 and effective starting from January, 2013. The unified law aimed to improve the overall legislative background of the field, though the questions still remained ( McGee 2014, Alagardova and Manuilova 2015, Pirveli 2015). According to the World Bank’s report of 2015, the recommendations of 2007 were partially addressed: “The 2012 A&A Law introduces differentiated financial reporting requirements, including adoption of the IFRS for SMEs” (Alagardova, Manuilova 2015, 12).

This was a major improvement and simplification of reporting requirements for small and medium entities. The implemented changes have shown the loyalty of Georgian government towards the establishment of strong corporate financial accounting framework, but this turned out not to be enough for timely fulfilment of the obligations taken by the EU Association Agreement of 2014. “Reforms in the area of financial reporting and auditing are complex and will require significant efforts and resources for their implementation in the country” (Alagardova, Manuilova 2015). Major critics was directed towards audit quality: auditors should be registered publicly, should be having a certified auditor’s status if willing to audit PIEs and their profile information should be publicly available. Also, the next law should address threats to auditor’s independence, and other potential conflicts of interests. To avoid auditor’s biasness, audit fees should have been disclosed publicly, similar to the EU practice.

Overall, despite of attempts, the regulation of the field has been relatively unsystematic for decades.

The Details of the Ongoing Reform

In June 2014, the EU and Georgia signed an Association Agreement. The agreement entered into force on July 1, 2016 and implied development of the existing Georgian legislation and its conformity with the EU acquis. The changes covered many fields, including the field of accounting and audit. In this context, Georgian government adopted the Action Plan for Financial Reporting and Auditing Reform which has resulted in the enactment of the Law of Georgia on Accounting, Reporting and Auditing as of June 8, 2016 (Law 2016).

The Law (2016) gave the birth to some marked changes. One of these was the establishment of the Service for Accounting, Reporting and Auditing Supervision (SARAS) – a subordinated agency operating under the Ministry of Finance of Georgia on June 24th, 2016. The main functions of this supervisor authority were set as follows: establishment of a state register for the auditors and audit firms; production of the financial and managerial reporting website of the enterprises; introduction of financial statements and audit standards as regulations, rules of action; monitoring the quality control system of the service provider; recognition of certification programs, examination processes and continuing education programs as well as monitoring of the persons implementing these services. SARAS aims to get acquainted to the best practices worldwide and adopt them in for local settings. Creating the supervisor authority laid the basis for the reform of the accounting and audit field in Georgia. The reform aims at developing capital and financial markets and improving the investment environment by ensuring transparency of reporting entities, which, in turn, protects the needs of external stakeholders relevant to the field. The reform targets to create reliable information source containing the financial and managerial data of the entities, which would also increase the credibility of audit (SARAS 2016).

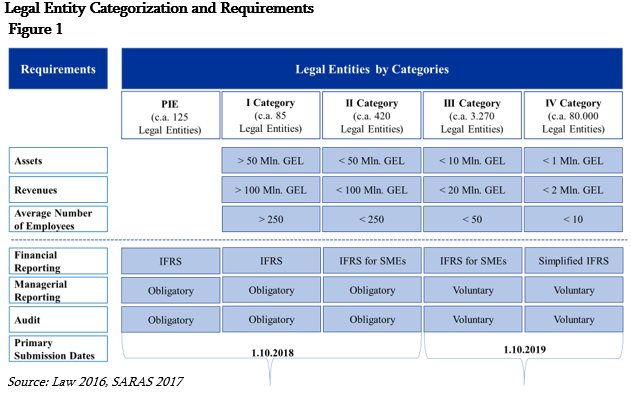

In order to lead the reform effectively and achieve the long-term goals, SARAS actively cooperates with international organizations: World Bank's Financial Reporting Reform Center (CFRR, part of the World Bank’s Governance Global Practice) based in Vienna; Asian Development Bank of Georgia; USAID; Good Governance Fund of Great Britain and EBRD, from which the World Bank CFRR group is the most actively involved party in supporting the reform. In 2016, the functions, structure and action strategies for SARAS were defined and allocated. During 2016, SARAS issued a number of important statutory acts and established an online registry for auditors, from which the statistical data on the registered insurers, their revenues or number of employees (among others) can be viewed by any interested parties. SARAS issued procedures for determining the conditions for auditor firm’s professional liability insurance and the amount of insurance, rules of electronic procedures, structure, forms, informational content and consumer’s identification procedures for the website and registry, as well as the rule of providing temporary authority for implementing audit of PIEs’ financial statements.New law has defined the status of a Public Interest Entity. According to it, a PIE is defined as follows: this is a legal entity which could be: (i) an accountable enterprise, whose securities are admitted to trading on a stock exchange in accordance with the Law of Georgia on Securities Market (ii) a commercial bank or a microfinance organization (iii) an insurer or investment fund and (iv) an entity defined as PIE by the government of Georgia (Law 2016).The major step was categorization of the entities. The law of 2016 defined four categories of enterprises (see Figure 1). The categories are assigned based on entities’ total value of assets, revenues and an average number of employees during the reporting period calculated on a consolidated basis at the end of the reporting period of the parent company. SARAS has recently mandated the public disclosure of audited financial statements of private sector entities in Georgia. Financial statements of PIEs and first category entities shall be prepared according to IFRS, while second and third categories apply IFRS for SMEs and the fourth category follows the "Simplified (temporary) Standard for Accounting for Small Enterprises" (approved by the resolution N9 of April 5, 2005 by the Committee of Accounting Standards at the Parliament of Georgia). II, III and IV category entities are allowed to use the standards applied for a one-step lower category. Groups of I and II categories shall report their financial, managerial (activity review, corporate managerial report and non-financial report) and audit reports of the financial year 2017 immediately, but not later than October 1st, 2018. Groups of the third and fourth categories shall report their consolidated financial statements of the financial year 2018 immediately, but not later than October 1st, 2019 (Law 2016). The reports should be submitted to SARAS, who, on its side, is supposed to review and then publish the reports on its web-site within 1-month.

Based on these requirements, about 80.000 legal entities of IV category and 3.270 legal entities of III category are requered to ‘go public’ by October 1, 2019. About 600 legal entities of I and II categories plus PIEs have already submitted their financial information by the end of 2018.

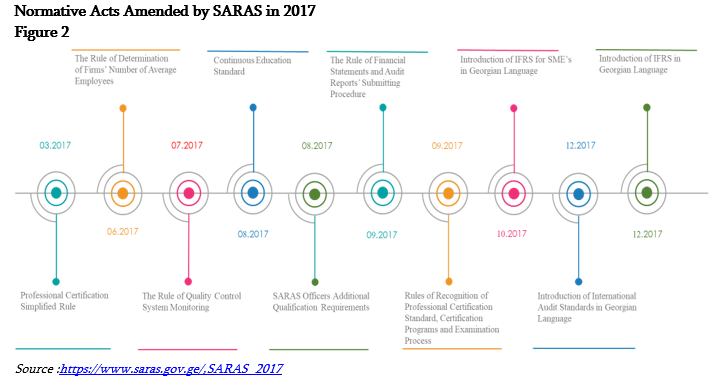

2017 was a fruitful year in terms of the enactment of normative acts, but also because SARAS has created and administered electronic web-site and portal for reporting on financial statements, management statements of subjects and payments towards the state in order to facilitate business transparency, economic analysis, as well as capital and credit markets development. This process started in January 2017 and lasted for the next 9 months. Totally 10 normative acts have been amended in 2017. Figure 2 shows the timeline of normative act amendments in 2017. Major changes related to the improvement of the quality of education of accountants and auditors. SARAS, based on EU directives, has established the standards of Professional Certification and Continuous Education. These include teaching, testing and certification of interested parties. For the purpose of maintaining the certified accounting qualifications, education program and legal basis for its implementation and recognition, on August 18, 2017, SARAS approved "Continual Education Standard". According to the standard, a certified accountant is obliged every year to comply with the continuing education requirements. SARAS also provides a registry of examination processes, professional certification and continuing education programs. Recognized programs are posted on the official website of the regulatory body. During the year, in accordance with the standard requirements, SARAS has recognized, officially registered and monitored three continuing education programs.

In order to determine the rule that non-certified experienced persons’ certification and monitor of the enforcement of this rule, on March 24th, 2017 SARAS approved “Simplified Rule of Professional Certification” that defines simplified test administration and procedures for professional certification of persons who have more than 7 years of relevant experience of acting as a transaction partner before the enactment of the law and are not certified accountants in accordance with the same law.

A particular focus of the reform has been put towards the role of professional translation in the process of establishment of international standards. Professional Accountants Ethics Code was translated into Georgian language by GFPAA and then was enacted by the regulatory body in 2017. To achieve a high-quality translation, a specific working group (Committee of Experts) has been created which is supposed to be staffed by experienced professionals in the field. SARAS approved the Georgian language versions of IFRS, IFRS for SMEs and International Audit Standards as officially accepted standards by the end of 2017. Translated standards as well as normative acts are placed on the official website of SARAS.

In response to World Bank’s report of 2015, relating to audit quality deficiencies, according to the new law, only formally qualified and officially registered auditors are able to conduct the audit of PIEs. The registry is public and the information published there (regarding the auditor or the audit firm) is accessible for any interested person. Registry requirements, which the auditors must meet, is defined by law and the additional information regarding the registration procedure is provided by the SARAS. Besides, according to the Law of 2016 (paragraph 5 & 6) PIEs and I category entities are obliged to submit the information about their audit and non-audit services.

In 2018 SARAS’s focus has shifted form the establishment of the regulatory base, towards the increase of the interested parties’ awareness. This has been mostly done through the establishment of different textbooks as well as conduction of trainings and informative meetings. The meetings targeted to rise the involved parties’ awareness have been attended by a wide range of stakeholders such as company managers and auditors, representatives of professional organizations, business associations, SME associations, academia, diplomatic corps, donors and international organizations. The held meetings aimed at providing important information to the audience and sharing the best practices of leading countries. The meetings were held in different regions of Georgia and focused on the amended legislation and reform details as well as the expected benefits, the goals of SARAS, essential innovations, the specifications of IFRS for SMEs, the necessity of introduction, the content and advantages of its use. The meetings have been largely coordinated, organized and financed by the World Bank CFRR and other Contracting Parties such as Good Governance Fund of Great Britain, USAID and EBRD.

In order to simplify the process of preparation of management reporting, SARAS has developed a "Managerial Reporting Manual", targeted for the PIEs as well as I and II category representatives. The manual is a wide-use, recommendation-oriented document that is based on the best practices and the latest international developments and does not generate new legal obligations. It establishes basic principles that protect enterprises' performance in the appropriate form and provide comparability.

In order to support homogeneity of the financial reports of IV category entities, SARAS on 26 June 2018 approved the "Financial Reporting Standard of Fourth Category Enterprises". The provisions of the relevant EU Act and the best international practice were taken into account in developing the standard. The standard is focused on simplicity and aims to reduce the costs of administrative expenditure for the fourth category enterprises. In the framework of the project, a consultative group was created which included accountants, revenue services, commercial banks, business associations, academic circles, professional organizations and private consulting companies. In order to detect the nature and complexity of the operations for the fourth category, the consultative group has in depth studied accounting practices of more than 60 enterprises. In the framework of the project, the experience of micro organizations from Estonia, the United Kingdom, Poland, Ireland and Singapore have been shared.

Within the framework of the Action Plan for Financial Reporting and Auditing Reform, the USAID, with the support of the World Bank and G4G, is implementing a program for promoting the standard of second and third enterprises. The program consists of the following main components: training of English- and Georgian-language trainers of IFRS and IFRS for SMEs and translations of IFRS Foundation’s textbooks and materials. Within the framework of the program, on 8-12 October 2018, the English language trainers training course was conducted. The training was conducted by the World Bank's International Consultant for Education and Training, Michael Wales, selected by the World Bank in the frames of the SFRR project, which has experience of trainings in similar countries. By the end of the year, training for English- and Georgian-language trainers have been organized and held by SARAS with support of the USAID and G4G. With this activity, the tutoring training is over. As a result, 88 trainers were trained, covering people from 14 regions. From 2019, the program for the end-users is expected to start. At the same time, the standard of training materials is translated and adjusted to Georgian reality (SARAS 2017).

These actions have been presumed to set the environment in which entities would be able to provide credible, standard-driven financial information to the market.

Descriptive Analysis

We have obtained descriptive statistics of 586 entities from their separate profile websites given at https://reportal.ge/ by using the AI scraper “Scrapestorm”. The visual analysis has been implemented by Microsoft Power BI.

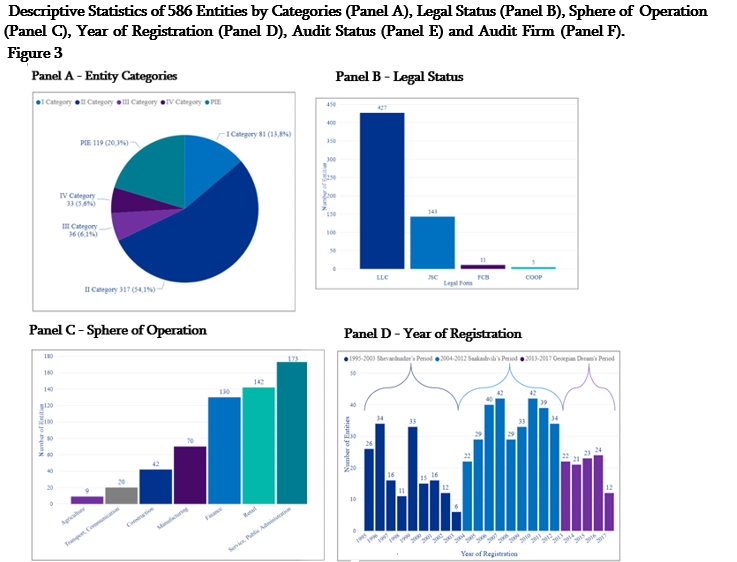

This section descriptively reviews the collected sample data of the private sector in Georgia. By January 2019, total of 586 entities have submitted their annual financial statements to SARAS. This information reveals what are the characteristics of the entities which obeyed the law and provided financial statements well-enough to pass the controlling by SARAS. Figure 3 shows the descriptive statistics of the sample by the following criteria:

- Entity Categories (Panel A),

- Legal Status (Panel B),

- Sphere of Operation (Panel C),

- Year of Registration (Panel D),

- Audit Status (Panel E) and

- Audit Firm (Panel F).

Entity Categories - Panel A

Entities belong to one of the five categories: I, II, III, IV and Public Interest Entities (PIEs). 81 entities (13.82%) belong to the I category, the majority of entities (317 – 54.1%) come from the II category, 36 and 33 entities belong to III and IV categories, respectively and 119 entities (20.31%) are the PIEs. Worth noting that, even though not required by the law until October 1, 2019, some of the III and IV categories entities have already submitted their financial statements a year earlier. Given in total about 83k entities, 69 (sum of third and fourth category) entities indeed constitute a very minuscule proportion, however, may also hint on the existence of a (small) good-will towards a volunteer publication at the market. We note that the largest entities satisfying at least two of the following three criteria: actives above 50 mln, revenues above 100 mln and the number of employees above 250 have significantly smaller share (about 25%) compared to the second largest category. In sum 180 PIEs have been registered at the official website, from which many of the entities do not anymore bear the ‘active’ status of an enterprise and as such 119 entities have submitted their reports. As it would have been expected, from 119 PIEs, 100 of them operate within the financial sector. That is, PIEs are mostly the banks, microfinance organizations and others. Overall, the given picture on entity categories could be an expected, but interesting one.

Legal Status - Panel B

Entities belong to one of the four legal status: Joint Stock Company (JSC), Limited Liability Company (LLC), Cooperative (COOP) and Foreign Company Branch (FCB). The most prevalently represented group is LLC, constituting 427 entities (72,87% of the sample) from total of 586. 143 (24,4%) entities are JSCs, and only minor 16 entities (2,73%) have legal status of either Cooperative or a Branch of Foreign Enterprise.

Sphere of Operation - Panel C

We have categorized entities by spheres of operation following the SIC rules. We have categorized entities by the following spheres: agriculture, mining and construction, manufacturing, transport and communication, retail, banking/finance, service and public administration. We note the most widely represented spheres are retail (142 entities), banking/finance (130 entities) and service (173 entities). A small portion of entities (9) are within the agriculture sector, while 70 entities are within manufacturing.

Year of Registration - Panel D

We note that after the minimum number of entities’ registration recorded in 2003, the number started to increase starting from 2004, reached its maximums (42 entities) in 2007 and 2010 and had a relatively decreasing tendency thereafter. These results adhere to the Georgia’s ranking changes within the ‘ease of doing business’ ranks. An average number of entities registered during the Shevardnadze period (1995-2003) has been 19, during Saakashvili’s period (2004-2012) - 39 and during the Georgian Dream’s period (2013-2017) now it stands at 20.

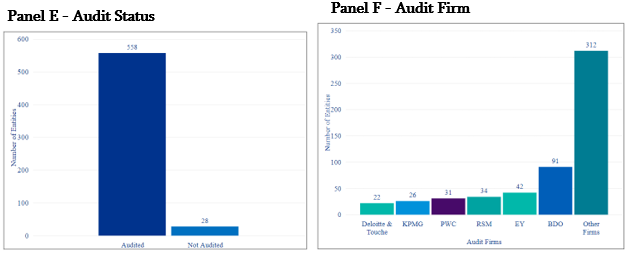

Audit Status - Panel E

Panel E shows whether entities have reported audited or non-audited financial statements. Only 28 (out of 586) financial statements are non-audited. That is, financial statements are audited in most of the cases and the rule is well-followed in this regard. Based on the regulation, III and IV category entities are not required to submit audited financial statements. Despite of it, out of 69 voluntarily submitted financial statements of III and IV category entities, 67 are audited. This may indicate that the entities who feel safe and healthy in terms of their financial fundamentals, do also bring an incentive to voluntarily publicize their financial reports. This would indicate that entities not only follow the regulation, but also target to some other interested parties (most likely the creditors – banks, as the capital markets are weak to say the least). We further note that out of 28 non-audited financial statements, the largest portion (11 statements) belong to PIEs. It is a small portion, but still a violation of the law.

As next, we would like to distinguish entities by their auditor firms. Here we note that 246 financial statements (44% of total) are audited by large auditor firms such as: KPMG, BDO, Deloitte & Touche, PWC Georgia, RSM Georgia, E&Y Georgia. 312 entities are audited by other, smaller players. This shows a considerable demand on a ‘qualitative’ audit services from the I and II category entities and PIEs. BDO has audited the largest number of entities (91). E&Y, RSM and PWC follow with the corresponding 42, 34 and 31 entities to have audited. Unreported statistics also reveal that most active clients of big audit firms were entities operating in banking/finance sphere. More precisely, 45% of the submitted reports from this sphere (54 reports) were audited by the big audit firms. From the perspective of firm categories, 38% of I category entities, 24% of II category entities and 29% of PIEs used the service of big audit firms. While III and IV category entities were not obliged to submit audit reports, 19% and 29% of them submitted financial reports audited by the big players. This again shows cooperation with big players and interest to the quality of audit, even if audit is not required.

It is worth noting that some entities voluntarily published their financial reports of 2016. Financial reports of 2016 were published by 148 entities out of about 83.300 total, which corresponds c.a. 0.18%. Most of the volunteering companies (79) were the PIEs. There were no entities reporting from the first category and there were only several (4) reports from the second category. 69 entities have volunteered from the third and fourth categories.

Implications and Estimations

As the world around changes in a systematic way, regulations are also subject to permanents changes. The field of Accounting and Audit in Georgia has been a subject of changes since country’s independence (starting from 1990s). Instrumental questions, however, have been remained unaddressed along the years. We note several aspects why the currently ongoing reform might be significantly different from any of its predecessor attempts. Theoretical review of the reform details has witnessed few aspects how the current changes may differ and may bring significant changes to field. First, we note that the currently ongoing changes align with the EU framework; that is, the processes are governed, manage, administered and financially supported by foreign parties that may already represent a crucial tool to achieve quality results. The law of 2016 is also aligned and based on the European framework and intensive debates/workshops are held which aim to monitor and plan the steps of a Georgian regulatory body, SARAS.

Second, it needs to be noted that the ongoing reform targets and fights, among others, against those weakness previously associated and strongly linked to Georgian accounting and audit field. That is, a clear classification of the entities has been set by the law, more focus is set on professional translation processes, an electronic system has been organized and administered, training courses have been organized and held by the regulatory body to ensure local accountants and auditors’ awareness on high-quality reporting fundamentals.

First descriptive statistics also reveal that almost all the mandated entities have submitted their reports of 2017. This in some cases required either caution or a sanction from SARAS. It is difficult to judge how timely entities have followed the requirements as SARAS itself played a mediator role and only after controlling/checking has published the reports publicly. Few noteworthy aspects are: almost half of the entities used the audit service of big 6 audit firms.

Prior literature has suggested that there are no particularly high expectations towards high quality accounting numbers in Georgia – within its banking and insurance sectors (World Bank Report 2007), at the Georgian Stock Exchange (Pirveli, Zimmermann 2015) and overall within the country (Pirveli 2014, 2015). On the one hand, in the absence of functional capital markets and the consequent incentives (e.g., target meeting/beating), there is no stimulus to play with earnings. On the other hand, however, corporate managers also do not input particularly high efforts in providing highly decision-useful accounting information as the overall demand on accounting numbers is moderate. In the absence of the capital market pressures, the demand may shift towards the banks. Banks in Georgia, however, base their crediting decisions on the amount of collateral and website visits (World Bank Report 2007). Prior literature has additionally shown that tax-incentives prevail over financial or managerial reporting incentives .

Consistent to these findings, we cautiously predict that the actively led accounting reform will bring positive outcomes to the field. The question remains: what time the reform would necessitate to bring the tangible and visible results to a playing field, however, we believe the reform would reflect into a better-quality financial information. The reform not only improves the awareness of the involved parties, but also increases the overall transparency of the private sector’s financial health and improves entities’ adherence to the dictates rules.

The findings are of high contribution in several ways. At a scientific level, this study contributes to the existing literature on accounting and audit system’s efficiency from an under-developed market’s perspective. At the regulatory level, the findings are of importance for the regulators in Georgia (to formulate appropriate policies, currently debated in the Parliament of Georgia) and in Europe. Finally, financial information users such as banks, investors and tax regulators may gain insights at what level the firm’s given fundamentals could be trusted within the Georgian private sector.

References:

- "Law of Georgia on Auditing." edited by Parliament of Georgia, 1995.

- "Law on the Regulation of Accounting and Financial Reporting." edited by Parliament of Georgia, 1999.

Accounting, Vol. 1, No. pp. 1-5. (in Georgian).

- Alagardova, G., and Manuilova, N. 2015. Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes on Accounting and Auditing, World Bank Report.

- Biddle, G.C., Hilary, G., and Verdi, R.S. 2009. "How Does Financial Reporting Quality Relate to Investment Efficiency?", Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 48, No. 2-3, pp. 112-131.

- Blundell-Wignall, A., and Atkinson, P. 2010. "Thinking Beyond Basel Iii", OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends, Vol. 2010, No. 1, pp. 9-33.

- Chumburidze, L. 2013. "Considerations on Accounting and Financial Reporting Audit (in Georgian).

- Cohen, D.A., Dey, A., and Lys, T.Z. 2008. "Real and Accrual-Based Earnings Management in the Pre-and Post-Sarbanes-Oxley Periods", The Accounting Review, Vol. 83, No. 3, pp. 757-787.

- Cosimano, T.F., and Hakura, D. 2011. "Bank Behavior in Response to Basel Iii: A Cross-Country Analysis", Vol. No. pp.

- Daske, H., Hail, L., Leuz, C., and Verdi, R. 2008. "Mandatory IFRS Reporting around the World: Early Evidence on the Economic Consequences", Journal of accounting research, Vol. 46, No. 5, pp. 1085-1142.

- DeAngelo, L.E. 1981. "Auditor Size and Audit Quality", Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 183-199.

- Feltham, G.A., and Xie, J.Z. 1992. "Voluntary Financial Disclosure in an Entry Game with Continua of Types", Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 46-80.

- Financial Statement Quality: First Evidence from the Georgian Stock Exchange, Shaker Verlag, Germany.

- Foster, G. 1981. "Intra-Industry Information Transfers Associated with Earnings Releases", Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 201-232.

- Francis, J., Nanda, D., and Olsson, P. 2008. "Voluntary Disclosure, Earnings Quality, and Cost of Capital", Journal of accounting research, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 53-99.

- Francis, J.R. 2004. "What Do We Know About Audit Quality?", The British Accounting Review, Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 345-368.

- Francis, J.R., Maydew, E.L., and Sparks, H.C. 1999. "The Role of Big 6 Auditors in the Credible Reporting of Accruals", Auditing: a Journal of Practice & Theory, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 17-34.

- Gal-Or, E. 1987. "First Mover Disadvantages with Private Information", The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 54, No. 2, pp. 279-292.

- Ge, W., and McVay, S. 2005. "The Disclosure of Material Weaknesses in Internal Control after the Sarbanes-Oxley Act", Accounting Horizons, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 137-158.

- Government, G. 2013. Socio-Economic Development Strategy of Georgia, Georgia 2020,

- Grossman, S.J. 1981. "The Informational Role of Warranties and Private Disclosure About Product Quality", The Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 461-483.

- Grossman, S.J., and Hart, O.D. 1980. "Disclosure Laws and Takeover Bids", The Journal of Finance, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 323-334.

- Group, W.B. 2007. Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes (Rosc) Georgia, Accounting and Auditing., World Bank Report.

- Gvaramia, N. 2014. "The Issues of Activity Accounting and Audit Regulation in Georgia", Economics and Management, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 619-624.

- Jensen, M.C., and Meckling, W.H. 1976. "Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure", Journal of financial economics, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 305-360.

- Kaciashvili, V. 2003. Peculiarities of the Formation and Regulation of Audit Activity at the Transitional Stage in Georgia. Finance Research Institute (in Georgian).

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R.W. 1998. "Law and Finance", Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 106, No. 6, pp. 1113-1155.

- Law. "Law of Georgia on Accounting, Reporting and Auditing." edited by Parliament of Georgia, 2016.

- Leuz, C., and Verrecchia, R.E. 1999. "The Economic Consequences of Increased Disclosure", Vol. No. pp.

- Li, H., Pincus, M., and Rego, S.O. 2006. "Market Reaction to Events Surrounding the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and Earnings Management", Vol. No. pp.

- Lobo, G.J., and Zhou, J. 2006. "Did Conservatism in Financial Reporting Increase after the Sarbanes-Oxley Act? Initial Evidence", Accounting Horizons, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 57-73.

- McGee, R.W. 2014. "A Comment on the Accounting and Auditing Law of Georgia", Business & Law, Vol. No. 3, pp. 11-13.

- Merton, R.C. 1987. "A Simple Model of Capital Market Equilibrium with Incomplete Information", The journal of finance, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 483-510.

- Milgrom, P.R. 1981. "Good News and Bad News: Representation Theorems and Applications", The Bell Journal of Economics, Vol. No. pp. 380-391.

- Myers, S.C., and Majluf, N.S. 1984. "Corporate Financing and Investment Decisions When Firms Have Information That Investors Do Not Have", Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 187-221.

- Pirveli, E. 2014. "Accounting Quality in Georgia: Theoretical Overview and Development of Predictions", International Journal of Business and Social Science, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp.

- Pirveli, E., and Zimmermann, J. 2015. "Time-Series Properties of Earnings: The Case of Georgian Stock Exchange", Journal of Business and Policy Research, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 70-96.

- SARAS. 2016. Annual Financial Statement, SARAS.

- SARAS. 2017. Annual Financial Statement, SARAS.

- Slovik, P., and Cournède, B. 2011. "Macroeconomic Impact of Basel Iii", Vol. No. pp.

- Verrecchia, R.E 1990. "Information Quality and Discretionary Disclosure", Journal of accounting and Economics, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 365-380.

- Verrecchia, R.E. 2001. "Essays on Disclosure", Journal of accounting and economics, Vol. 32, No. 1-3, pp. 97-180.

- Wagenhofer, A. 1990. "Voluntary Disclosure with a Strategic Opponent", Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 341-363.

- Zhang, I.X. 2007. "Economic Consequences of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002", Journal of accounting and economics, Vol. 44, No. 1-2, pp. 74-115.

- Zimmermann, J., and Werner, J. 2013. Regulating Capitalism?, Palgrave Macmillan UK, UK.

საქართველოში მიმდინარე ბუღალტერიისა და აუდიტის რეფორმა: თეორიული და აღწერილობითი ანალიზი

ნებისმიერი ეკონომიკური რეფორმა ორი ჭრილით განიხილება: ა) რამდენად კარგი ხარისხისაა რეგულაციური ჩარჩო და ბ) რამდენად კარგად ხდება აღნიშნული რეგულაციური ჩარჩოს რეალობაში აღსრულება. ხარისხიანი რეგულაციის ქონას მხოლოდ და მხოლოდ მაშინ აქვს აზრი, თუ კი მისი რეალობამდე მიტანაც ასევე ხარისხიანად არის უზრუნველყოფილი. სხვა სიტყვებით რომ ვთქვათ, ორივე მათგანი - რეგულაციის ხარისხიც და მისი აღსრულების დონეც - აუცილებელი, მაგრამ არასაკმარისი პირობაა რეფორმის წარმატებულად მიჩნევისათვის. მხოლოდ მათ ერთობლიობას შეუძლია რეფორმა წარმატებულად აქციოს.

საქართველოს მთავრობის მიერ 2016 წლის 8 ივნისს ამოქმედებული „საქართველოს კანონში ბუღალტრული აღრიცხვის, ანგარიშგებისა და აუდიტის შესახებ“, გათვალისწინებულია მსოფლიო ბანკის მიერ 2007 და 2015 წლებში გაჟღერებული რეკომენდაციები, თანაც კანონის მიმდინარე ვერსია მის ყველა წინამორბედ ვერსიაზე უკეთესია.

რაც შეეხება კანონის აღსრულების ხარისხის შეფასებას მას დრო და შესაბამისი მონაცემები სჭირდება. ვეყრდნობით რა ევროპულ გამოცდილებას და ვიღებთ რა ფინანსურ თუ ადმინისტრაციულ დახმარებას სხვადასხვა საერთაშორისო ორგანიზაციიდან (CFRR World Bank, EBRD, G4G UK, USAID), შედარებით მარტივია ჩამოვაყალიბოთ ჯანსაღი რეგულაციური ბაზა. თუმცა, ადეკვატურად და დროულად მივყვეთ ამოქმედებულ კანონებს, შედარებით მეტ გამოწვევას გულისხმობს.

ბუღალტერიისა და აუდიტის დარგში მიმდინარე ცვლილებები თავისი მასშტაბურობით უპრეცენდენტოა ქვეყნის ისტორიაში: 2018 წლის 1 ოქტომბრამდე ფინანსური ანგარიშგების გასაჯაროება მოეთხოვა პირველი და მეორე კატეგორიისა და საზოგადოებრივი დაინტერესების პირების დაახლოებით 600-700 იურიდიულ ერთეულს, ხოლო 2019 წლის 1 ოქტომბრამდე საჯაროობის საზღვრის გადაკვეთა მოუწევს მესამე და მეოთხე კატეგორიის საწარმოებს - დაახლოებით 83000 იურიდიულ ერთეულს.

წინამდებარე სტატია პირველია, რომლის ფარგლებშიც ამოღებულ იქნა იმ საწარმოთა აღწერილობითი ინფორმაცია, რომლებმაც საკუთარი ფინანსური ანგარიშგებები 2018 წელს ფინანსთა სამინისტროს ბუღალტერიის, ანგარიშგებისა და აუდიტის ზედამხედველობის სამსახურს წარუდგინეს და გაასაჯაროვეს. ინფორმაცია ამოღებულ იქნა 2019 წლის 15 იანვრიდან 19 იანვრის ჩათვლით. ინფორმაციის ავტომატურად ამოსაღებად გამოყენებულ იქნა პროგრამები: “Link Klipper” და “Scrapestorm”. დაკვირვების ობიექტმა შეადგინა 586 საწარმო.

საწარმოთა 20% სდპ-ა, 14% - I კატეგორიის საწარმო და 54% - II კატეგორიის საწარმო. საწარმოთა 12% III და IV კატეგორიას წარმოადგენს - მათ 2018 წელს საერთოდ არ ევალებოდათ ინფორმაციის წარდგენა. სავარაუდოდ, ეს მესამე და მეოთხე კატეგორიის საწარმოები ან კრედიტორებთან კომუნიკაციაზე აკეთებენ აქცენტს ან მათთვის მნიშვნელოვანია სახელმწიფოსთან გადასახადების გადახდის კუთხით გამართული კომუნიკაცია. ასევე, არსებობს იმის ალბათობა, რომ ამ საწარმოებმა აქტივების უფრო ზუსტად (შემოსავლების სამსახურის მიერ მოწოდებულ ინფორმაციასთან შედარებით) დათვლის შედეგად თავი II კატეგორიას მიაკუთვნეს და თავი ვალდებულად მიიჩნიეს წარედგინათ ანგარიშგებები. თუკი, ამ საწარმოებს ისედაც მზად ჰქონდათ ფინანსური ანგარიშგებები, ნებაყოფლობით მათი გასაჯაროებით, მომდევნო წლისთვის არამარტო პრაქტიკა გაიარეს, არამედ შესაძლოა კრედიტორების (დაინტერესებული მხარეების) თვალში უფრო სანდოებად / გადახდისუნარიანებად წარმოჩინდნენ.

427 საწარმო შპს-ა, 143 - სააქციო საზოგადოება, 16 - ან უცხოური საწარმოს ფილიალი ან კოოპერატივი. ოპერირების სფეროს მიხედვით (კლასიფიცირება მოხდა SIC კლასიფიკაციის მიხედვით), როგორც მოსალოდნელი იყო, ყველაზე გავრცელებულია მომსახურებისა და საჯარო ადმინისტრირების სფერო; შემდეგ - ვაჭრობა/გადაყიდვა; შემდეგ კი - საფინანსო სექტორი. მოლოდინების შესაბამისად, მცირეა წარმოების სფეროში მოქმედი საწარმოების რაოდენობა (70). მხოლოდ 9 საწარმოა სასოფლო-სამეურნეო სექტორიდან.

წლების მანძილზე ვადევნებდით რა თვალს ბიზნესის კეთების სიადვილის რეიტინგს, მხოლოდ 2006 წელს საქართველომ 75 პოზიციით წაინაცვლა წინ წინა წელთან შედარებით. 2005-2010 წლებში კი მსოფლიო ბანკმა საქართველო ლიდერ რეფორმატორ ქვეყნად დაასახელა ამ კუთხით. რეიტინგში ლიდერული პოზიციები შენარჩუნებულ და გაუმჯობესებულ იქნა ბოლო წლებშიც. რეიტინგების საპირისპიროდ, ნაკლებად თუ გვინახავს რეალური მონაცემები თუ რა დროს რამდენი ახალი საწარმო რეგისტრირდებოდა. როგორც ვხედავთ, საშუალოდ 19 და 20 ერთეული რეგისტრირდებოდა 1995-2003 და 2013-2017 წლებში, ხოლო 39 ერთეული - 2004-2012 წლებში.

დაბოლოს, ანგარიშგებების 95%-ზე მეტი აუდიტირებულია. საინტერესოა, რომ არა-აუდიტირებული ანგარიშგებების მნიშვნელოვანი წილი მოდის სდპ-ებზე, რომელთაც ევალებოდათ აუდიტირებული ანგარიშგებების წარდგენა. ასევე, III და IV კატეგორიის საწარმოების მიერ ნებაყოფლობით წარდგენილი რეპორტების სრული უმრავლესობა (69-დან 67) აუდირებულია. აღნიშნული დადებით სიგნალს გვაწვდის ნებაყოფლობით გადადგმული ნაბიჯების კუთხით, თუმცა ისიც უნდა გვახსოვდეს, რომ 67 საწარმო მიზერული რიცხვია III და IV კატეგორიის საწარმოების მთლიანი კონტინგენტის (დაახლოებით 83000 ერთეული) კვალობაზე. აუდიტირებული ანგარიშგებების 44% აუდირებულია დიდი ექვსეული აუდიტორი ფირმების (Deloitte & Touche, KPMG, PWC Georgia, RSM Georgia, E&Y Georgia და BDO) მიერ. ხოლო დანარჩენი - პატარა მოთამაშეების მიერ. ანგარიშგებათა ყველაზე დიდი წილი (91 ანგარიშგება) აუდირებულია BDO-ს მიერ.

კანონის თანახმად, ზედამხედველობის სამსახური თავად იტოვებს 1-თვიან ვადას, რათა წარდგენილ დოკუმენტაციას გაეცნოს და შემდეგ გაასაჯაროვოს. შესაბამისად,

ძნელია მსჯელობა იმაზე, თუ რამდენად დროულად წარადგინეს საწარმოებმა ფინანსური ანგარიშგებები. დაკვირვებამ აჩვენა, რომ საწარმოების ფინანსური ინფორმაცია ნაბიჯ-ნაბიჯ ემატებოდა 1 ოქტომბრამდეც, მას შემდეგაც და არ შეწყვეტილა დღემდე - 2019 წლის მარტის მდგომარეობით. ამის შესაბამისად ზედამხვედველობის სამსახურში აცხადებენ, რომ დაახლოებით 40 საწარმოს გასაჯაროებას კვლავ ელოდებიან. თუმცა გასაჯაროების ასეთ პროცესს არ შეიძლება ეწოდოს ზედმიწევნით დროული. საწარმოთა ნაწილმა მხოლოდ გაფრთხილებისა და ფულადი სანქციის (ერთმაგი ან ორმაგი) დაკისრების შემდეგ წარადგინაფინანსური ანგარიშგებები. კანონის თანახმად, ფინანსური ანგარიშგების წარმოუდგენლობა იწვევს IV, III, II, I კატეგორიის საწარმოებისა და სდპ-ებისთვის შესაბამისად - 500, 1000, 5000, 10000 და 10000 ლარით დაჯარიმებას, ხოლო 1 თვის ვადაში შეცდომის გამოუსწორებლობა, ამავე ოდენობით სანქციის გაორმაგებას.

ასევე ძნელია მსჯელობა კომპანიების ზუსტ რაოდენობაზე, რომელთაც ევალებოდა 2018 წლის 1 ოქტომბერს ფინანსური ანგარიშგების წარდგენა. საწარმოთა კლასიფიცირების მიზნით, ზედამხედველობის სამსახური იყენებს შემოსავლების სამსახურის ინფორმაციას აქტივების მოცულობასთან მიმართებაში. შემოსავლების სამსახურს ინფორმაცია გააჩნია საწარმოთა მხოლოდ იმ აქტივებთან მიმართებით, რომლებიც ქონების გადასახადით დაბეგვრას ექვემდებარება. აღნიშნული სრულად არ ასახავს საწარმოთა მთლიანი აქტივების სიდიდეს. შესაბამისად, ხდება იმ საწარმოთა მიახლოებითი (და არა ზუსტი) ოდენობის განსაზღვრა, რომლებსაც უწევდათ ფინანსური ანგარიშგების წარდგენა უკვე 2018 წლის 1 ოქტომბერს.

როგორც ზედამხედველობის სამსახურში აცხადებენ, ვალდებულ საწარმოთა 90%-ზე მეტმა გაასაჯაროვა საკუთარი ფინანსური ინფორმაცია. აღნიშნული, კანონის აღსრულების საკმაოდ კარგი მაჩვენებელია, განსაკუთრებით კანონის ამოქმედების პირველი წლისთვის. საწარმოთა იმ მცირე ნაწილს, რომელიც კანონს არ დაემორჩილა, სავარაუდოა, რომ ან მიზნობრივად არ სურდა საკუთარი ფინანსური დეტალების სახალხოდ გამომზეურება, ან მათ უკვე ორჯერ მოუწიათ ფულადი ჯარიმის (სანქციის) გადახდა და იმდენად რამდენადაც, სიტუაცია მეტად ვეღარ დაუმძიმდებოდათ, მათთვის აზრი აღარ ჰქონდა ფინანსური ინფორმაციის მომზადებას, აუდიტის ხარჯების გაღებას და ფინანსური ინფორმაციის გასაჯაროებას. სავარაუდოა, რომ იმ საწარმოებს, რომლებმაც ფინანსური ინფორმაცია მიზნობრივად არ გაასაჯაროვეს, ან არ სურდათ საკუთარი კონკურენტული სტრატეგიის საჯაროდ გამოტანა, ან მათი ფინანსური ანგარიშგებები შეიცავდა არა-სიმართლის ამსახველ (მიზნობრივად მანიპულირებულ ან კვალიფიკაციის დეფიციტის გამო შეუსაბამოდ მომზადებულ) ინფორმაციას.

აღნიშნულიდან შეგვიძლია დავასკვნათ, რომ კანონი არაზედმიწევნით დროულად, თუმცა დადებითად მიმდინარეობს აღსრულების კუთხითაც. მთავარი კითხვა არის ის, თუ რა წერია გასაჯაროებულ ფინანსურ ანგარიშგებებში, რამდენად მაღალია მასში მოწოდებული ფინანსური ინფორმაციის ხარისხი, რათა მომხმარებელს ეფექტიანი გადაწყვეტილების მიღებაში დაეხმაროს. მაკროეკონომიკურ დონეზე კი, საინტერესოა, თუ რას მოუტანს მიმდინარე რეფორმა საქართველოს ეკონომიკას. წაადგება კი ის ქვეყანას მოიზიდოს მეტი უცხოური ინვესტიცია, განავითაროს კაპიტალის ბაზრები, შეამციროს უმუშევრობა და გაზარდოს მთლიანი სამამულო პროდუქტი მოსახლეობის ერთ სულზე? ამ კითხვებზე პასუხის გასაცემად მეტი დრო, მონაცემთა ბაზები და სიღრმისეული ანალიზია საჭირო.