Referential and Reviewed International Scientific-Analytical Journal of Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Faculty of Economics and Business

The Role of Culture in Choosing a Tourism Destination (Case Study: Old Tbilisi, Georgia)

doi.org/10.52340/eab.2024.16.03.10

Although limited investigation was undertaken to delve into the significance of cultural worldview and authenticity within a goal-oriented behavioral approach, the current study analyzed tourism innovation's role in determining whether cultural worldview, authenticity, and tourism innovation significantly influence the decision-making process concerning visits to cultural tourism destinations. The statistical population of this research included Iranian travelers who visited Georgia, particularly in the Old Tbilisi region, a randomly selected sample of 384 individuals received and completed questionnaires for the research. The findings were assessed through structural equation modeling conducted via AMOS software. Contrary to expectations, the study revealed that cultural worldview has a lower role in the goal-oriented behavioral approach to creating the behavioral intention of Iranian tourists to visit old Tbilisi. There is no significant effect on the subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and positive anticipated emotion. Results indicated that the cultural worldview only affects attitude and negative anticipated emotions. However, authenticity proved influential in all the components of the goal-oriented behavioral approach. The study also highlighted that attitude, perceived behavioral control, and positive and negative anticipated emotions significantly influence the desire to visit. Moreover, the findings indicated that tourism innovation does not impact the desire to visit.

Keywords: Goal-oriented behavioral approach (GBA), Cultural worldview (CW), Authenticity (AU), Tourism innovation (TI), Old Tbilisi

JEL Codes: L83, L88, L

Introduction

Heritage tourism stands out as a prominent aspect of cultural tourism, providing visitors the chance to actively participate in various cultural activities, landscapes, performances, cuisine, and handicrafts that represent both the past and present (Chhabra et al., 2003). The significance of incorporating cultural and educational activities into travel experiences by offering a platform for learning experiences across diverse cultures (Wilson, 1986). Two main reasons for recognizing culture's significance in travel and tourism research. Firstly, tourists can immerse themselves in a culture, gaining firsthand observations, emotional connections, and sensory experiences, all contributing to the overall tourism experience (Kang et al., 2016). Secondly, culture is vital in influencing the tourists' attitudes, motives, choices, and behaviors (Ben-Dalia et al., 2013). In summary, understanding culture within the context of travel and tourism research is vital due to its direct impact on the tourism experience and its influence on tourists' attitudes and behaviors.

CW, a relatively recent concept, has been subject to empirical examination within the tourism domain, focusing on individuals' belief systems concerning their cultures (Choi & Fielding, 2016). Despite the prevalent focus on topics such as home-stay experiences (Musa et al., 2010) and engaging in experiences of staying at temples (Song et al., 2015), as well as other unconventional tourist settings, insufficient research exists regarding how the concept of CW is utilized within diverse cultural contexts (Wei et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2016). Additionally, Wei et al. (2020) research investigated how CW relates to cultural experiences in natural tourist sites. They recommended an exploration of tourist encounters across various cultural heritage locations as well. Throsby (2003) established the foundation of CW on a range of cultural values with multiple dimensions. The values serve as guiding ideals for societies and communities. How tourists perceive and communicate about culture shapes their CW, as highlighted by Matsumoto (2006). The perceptions, in turn, impact their choices and actions, as explored by Kang et al. (2016). The CW and life experiences of respondents showed significant divergence concerning their place of residence (Kang et al., 2016).

Apart from the context of tourism, individuals utilize AU as a measure for assessing a wide array of products and experiences (Newman, 2019, p. 8). Specifically, the AU maintains interconnected relationships, intertwining individuals, places, and objects within the same world (Moore et al., 2021). Similarly, CW and AU have emerged as noteworthy elements in foreseeing the anticipated behaviors of tourists participating in heritage tourism (Lee et al., 2020).

Rogers (1962) describes TI as a structure influencing Behavioral intention in a way that increases the desire to accept new services or products. TI can be a catalyst, prompting individuals to seek information, make reservations, and facilitate payments for their chosen tourism destinations (Kim et al., 2019(.

The principal goal of the present research is to bridge the gap in previous studies utilizing GBA. The study mainly develops the foundational GBA by combining CW and AU as two psychological precursors of the GBA framework. The research seeks to explore how TI influences the behavioral intention of tourists by further developing the GBA and adding another structure to the proposed conceptual model. It also intends to use a developed GBA to analyze tourists' Behavioral intention. The primary GBA is very suitable for this purpose (Han & Ryu, 2012; Meng & Choi, 2016), but essential elements were neglected in this model. Hence, the goal of the research is to advance this approach specifically within the realm of tourism destinations and the behavioral intentions of tourists by deepening the existing paths in this model and adding new variables such as CW, AU, and TI, enhancing the clarity and comprehension of the behavioral intentions of tourists and helping to predict Behavioral intention better. Therefore, the significant issue of this research is to clarify the behavioral intentions of travelers to visit a tourist destination. Addressing this issue and comprehending the factors that impact the Behavioral intention of tourists when visiting a particular tourist destination is very important in planning and marketing for tourist destinations and brings operational value to the tourism industry (Crompton & Ankomah, 1993).

In this study, the Old Tbilisi region, which was registered in the UNESCO World Heritage List back in 1993, is considered a tourist destination for Iranians. This is an area that can be regarded as an attractive destination for Iranian tourists. Therefore, evaluating what factors explain the behavioral intention of Iranians toward this tourist destination can be exciting and helpful in determining travel strategies for this tourist destination as well as providing services to potential tourists of this tourist destination. The study can enhance the advancement of literature concerning cultural tourism significantly, the development of GBA, deeper comprehension of the role of CW, AU, and TI in tourism in travel decision-making, and acquaint tourism activists with some of the drivers of cultural tourism.

Literature Review

Cultural Worldview (CW) and Goal-Oriented Behavioral Approach (GBA)

CW could play a pivotal role as a predictor and enhancer of understanding Behavioral intention within the framework of heritage tourism. It could also serve as an indicator of Perceived behavioral control (Lee et al., 2021). According to Triandis (1989), culture reflects the personal perceptions of individuals within their social environment. It was revealed that there is a favorable association between Subjective norm and cultural value, for instance, collectivism, leading to the acceptance of consumer e-commerce (Pavlou and Chai, 2002). Negative anticipated emotion was described as a sense of failure in reaching the goal (O'Sullivan and Strauser, 2009). On the other hand, Positive anticipated emotion is seen as an indicator of success in achieving the destination. Lee et al. (2012, 2018) further emphasized that Negative anticipated emotion is closely associated with negative expressions. Kountouris and Remoundou (2016) emphasize the importance of Attitude in comprehending Behavioral intention and assessing tourist destinations. Specifically, CW has a notable influence on the components of GBA (Attitude, Subjective norm, and Perceived behavioral control) (Lee et al., 2020). In summary, Richards (2018) underscores that tourists' perceptions of specific cultures are molded by their observations, interactions with local communities, and firsthand experiences.

Authenticity (AU) and Goal-Oriented Behavioral Approach (GBA)

Even though AU and consumption are closely related in practical terms, studies that began in the 1990s have only focused on the brand AU (Kososki & Prado, 2017). The outcomes of research conducted by Girish and Lee in 2020 contributed to an enhanced comprehension of how AU intersects with Attitude, Subjective norm, and Perceived behavioral control, consequently impacting Behavioral intention. Similarly, Shen (2014) discovered a positive connection between AU, and Perceived behavioral control shedding light on its role in shaping tourists' intentions to revisit traditional local events. According to Jang et al. (2012), AU correlates positively with Positive anticipated emotion, influencing Behavioral intention. Additionally, Ko and Choi (2020) emphasize the substantial influence of AU on positive emotions and emotional commitment, and AU positively influences the components of GBA (Attitude, Subjective norm, and Perceived behavioral control) (Lee et al., 2020). In summary, Tourism as a pursuit removed from the confines of everyday life, offers tourists chances to unwind, engage in self-reflection, and partake in genuine encounters. Thus, it’s widely recognized among managers that the perceived AU of a tourism experience serves as a fundamental draw for tourism destinations.

Goal-oriented Behavioral Approach (GBA) and Behavioral Intention (BI)

In tourism studies, a connection has been established between attitudes and the advancement of tourism (Gursoy et al., 2019). GBA assumed that Attitude, Perceived behavioral control, Positive anticipated emotion, and Negative anticipated emotion increase DE, subsequently encouraging residents' intention to conserve heritage actively (Lee et al., 2021). Furthermore, it was discovered that the components of the GBA are positively associated with DE. Consequently, it substantially impacts the Behavioral intention (Lee et al., 2020). Similarly, Attitude, Subjective norm, and Perceived behavioral control are the direct drivers of Behavioral intention (Ajzen & Driver, 1992). On the other hand, the balance between Positive anticipated emotion and Negative anticipated emotion for achieving the goal or failure consistently holds a significant role in comprehending future intentions and behaviors (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2004). Specifically, Perceived behavioral control, Positive anticipated emotion, Negative anticipated emotion, and the notion of Subjective norm were essential factors that influenced the tourism intention of travel (Song et al., 2017). A study by Hamid, S., & Bano, N. in 2021 emphasized that Attitude and Perceived behavioral control are essential factors in forecasting Behavioral intention.

Tourism Innovation (TI) and Behavioral Intention (BI)

TI is identified as a factor that impacts behavior, leading to an increased desire to embrace a new product or service (Hirschman, 1980). TI has been demonstrated through empirical studies to be a factor that facilitates travelers (Kim et al., 2019). Roehrich (2004) divides innovation into two parts: Life innovation, which mainly analyzes interest and desire for any novelty, and the other is adoption innovation, which focuses on the acceptance of new products. Goldsmith & Hofacker (1991), as critics of the innovation of life for power, coined that a new scale called innovation in a limited domain of interest can be used to predict ~domain-specific innovation~, its low prediction in specific products. The researchers supported this concept by verifying that innovation particular to the domain is a more potent predictor of innovative behavior than innovations in other areas (Roehrich, 2004; Hoffmann & Soyez, 2010; Bartels & Reinders, 2011). Noh et al. (2014) examined the outlook and proactive behaviors of the early adult age range concerning recently launched products. They found that affluent, innovative consumers were significantly eager to purchase innovative and novel products. Couture et al. (2015) also used this structure in their study, demonstrating its noteworthy impact on the tourists’ behavior.

Desire (DE) and Behavioral Intention (BI)

Possessing positive beliefs alone is insufficient to guide behavior entirely (Bagozzi and Peters, 1998). While positive thoughts contribute to shaping Behavioral intention, additional factors significantly influence whether the behavior will be done. On the other hand, various components of GBA have positive relationships with DE. Consequently, it substantially impacts Behavioral intention (Lee et al., 2020). Furthermore, Positive anticipated emotion plays the most crucial role in shaping consumer DE (Chiu & Cho 2022). Moreover, when individuals have strong desires related to tourism experiences, they are interested in expressing a higher Behavioral intention (Kim and Hall, 2019; Lee et al., 2018), and all the components of GBA demonstrate substantial predictive power for both DE and Behavioral intention (Meng & Choi 2016).

2.6. Old Tbilisi

Tbilisi serves as the capital and the most populous city of Georgia. Old Tbilisi denotes the historical sections of Tbilisi. While it has traditionally been the city's oldest area, it wasn't until 2007 that it gained recognition as an official administrative district. The city is located on both sides of the Matkvari River in the southeast of Europe. Tbilisi was founded in the 5th century by Vakhtang I, the king of ancient Georgia or Iberia, and it was named ~Tbilisi~ (derived from the word Tbili meaning hot) because of its hot springs. The location of Tbilisi, on the east-west route, has made this city the connecting point of various rival empires, and today, it guarantees it an essential route for the world's energy and business projects. The up-and-down history of Tbilisi can be understood from its architecture, which is a combination of medieval architecture, neoclassical architecture, and Stalinist architecture. Throughout history, Tbilisi has been home to various peoples with different races, cultures, and religions, but today, from a religious point of view, it is considered one of the Eastern Orthodox Christian cities.

Hypotheses and Conceptual Model

According to the proposed theoretical foundations, this research seeks to test the following hypotheses:

1) CW significantly affects the components of the GBA for visiting old Tbilisi.

2) AU significantly affects the components of the GBA for visiting Old Tbilisi.

3) The components of the GBA significantly affect the Desire to visit Old Tbilisi.

4) TI significantly affects the Desire to visit old Tbilisi.

5) The Desire to visit Old Tbilisi significantly affects the Behavioral intention to visit Old Tbilisi.

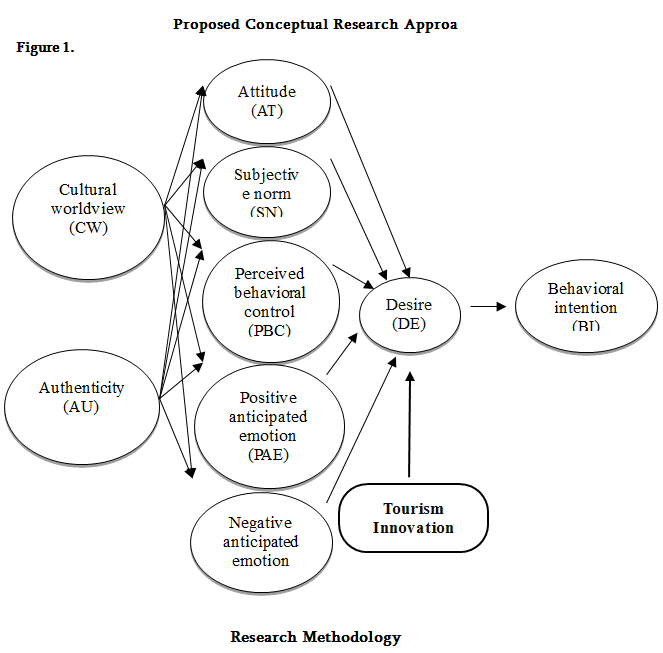

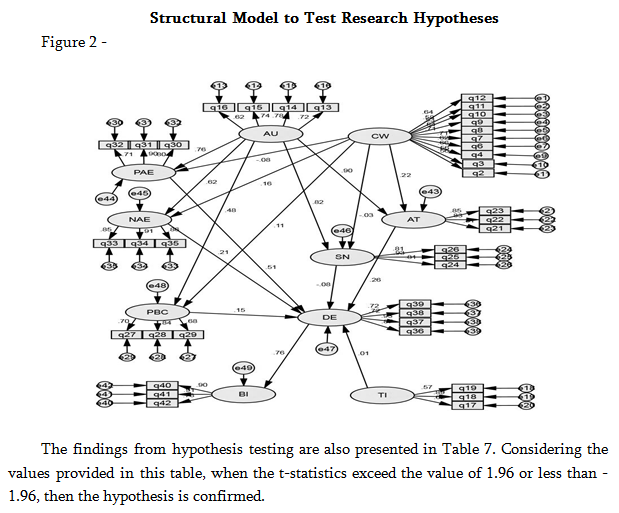

In Figure 1, the relationships explained in the research hypotheses and variables can be seen. Following the GBA, the variables of CW, AU, and TI are included in the model to develop the GBA. The initial model is according to the study of Lee et al. (2020), and by examining the previous studies, the variable innovation has been included in the GBA to develop this model further and provide TI. In this approach, Attitude, Subjective norm, Perceived behavioral control, Positive anticipated emotion, and Negative anticipated emotion are the components of the primary GBA. The variables of CW, originality, and TI are independent variables introduced into the initial model to advance the GBA to help explain the Desire and BI of Iranian tourists visiting Old Tbilisi. The proposed conceptual approach is presented by reviewing the previous literature and developing the GBA, and this study intends to use this GBA to explain the Desire and Behavioral intention of Iranian travelers in the tourist area of Old Tbilisi and evaluate which of the introduced components better predicts their Desire and Behavioral intention to visit the tourist destination of Old Tbilisi.

How to Measure Variables

CW represents the assessment of destinations by visitors, shaped by their collective values and convictions regarding their culture (Thompson et al., 1990). The variables in the study include six dimensions of identity preservation (intangible dependence), tangible dependence, understanding of concerns, acknowledgment of cultural values, consciousness of potential cultural damage, and safeguarding of heritage.

The 12-item questionnaire (Kang et al., 2016) was used to operationalize this variable, and two items were considered for each of the dimensions: preservation of identity, tangible attachment, understanding of concerns, acknowledgment of cultural principles, consciousness regarding potential cultural damage, and the safeguarding of heritage.

Originality: In the study conducted by Kolar and Zabkar (2010), AU was defined as how real tourists derive enjoyment from their cultural experiences. This variable is adjusted using a 4-item questionnaire derived from the studies of Gerish and Lee (2019), Meng and Choi (2016), and Kolar and Zebkar (2010).

TI: This concept relates to how much travelers desire to visit new tourist destinations (Huseynov et al., 2020). The variable has been prepared using a 4-item questionnaire derived from the study conducted by Kotar et al. (2015) and Huseynov et al. (2020).

GBA: This model is utilized for comprehending the various aspects of decision-making processes. The primary components are Attitude, Subjective norm, Perceived behavioral control, Positive anticipated emotion, Negative anticipated emotion, Desire, and BI (Lee et al., 2020). The elements were operationalized using a 21-item questionnaire derived from the study by Lee et al. (2020).

Desire: This concept is a motivational resolution for behavioral intention. Individuals form their emotions based on the anticipated result of action before engaging in the current behavior (Bagozzi and Peters, 1998). The concept has been measured in the present study using a 4-item questionnaire from the investigation carried out by Lee et al. (2020).

Behavioral intention: It means the willingness of a person to engage in a particular action. Behavioral intention can be regarded as an immediate indicator of actual behavior (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). The concept is used in the present study using a 3-item questionnaire derived from Lee et al. (2020).

Population and Statistical Samples and how to Collect Data

The statistical population of the present research is Iranian tourists who have traveled to Georgia and the old Tbilisi region. The target population has been identified through a tourism agency that provides travel tours for Georgia. Three hundred eighty-four people were selected as a sample population using Cochran's formula, and the questionnaires were distributed among the tourists of Tbilisi’s destination through a completely random sampling method. This process lasted until it reached the number of 384 complete questionnaires.

Measuring Questionnaire Validity and Reliability

The questionnaire validity has been asserted via content validity (expert validity) using either the CVR index or the Lauche coefficient. Due to the number of evaluators (10 people), the minimum acceptable CVR is 0.62, and all subjects obtained higher than this value. So, according to the experts, the questions were fair, and the validity of the measuring tool (questionnaire) was affirmed. Reliability was estimated using the internal consistency method, Cronbach's alpha, and considering that 30 initial questionnaires were pre-tested among the sample members and all the variables had Cronbach's alpha coefficients higher than 0.7, falling within the desired range for reliability.

Data Analysis Method

Inferential statistical methods were used to test the hypotheses. For this purpose, tests were first performed by default, and structural equation modeling was done with validation techniques and then using AMOS software. The fit measures for the model also assured that the findings from the confirmatory factor analysis were reliable. The model used for measurement has been converted into a structural model to assess how independent variables affect the dependent variable, whose fit indices also indicate the desirability of the model and the reliability of its results.

The Findings

Demographic Features

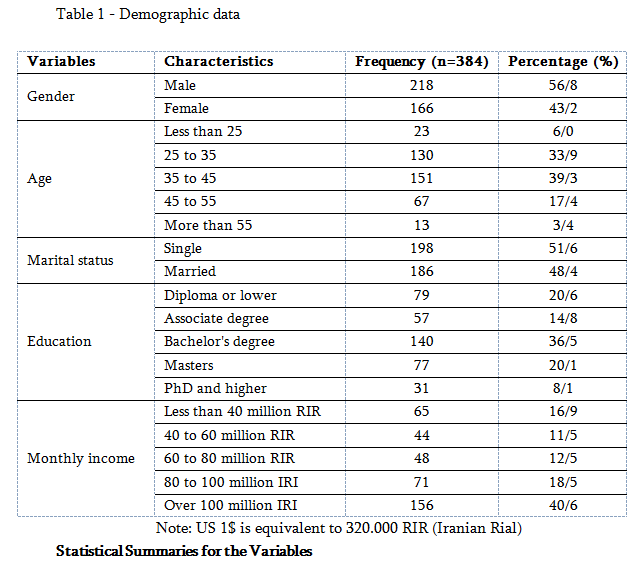

Table 1 indicates the attributes of the survey participants, in which the number of men is 56.8%, women are 43.2%, 39.3% are between 35 and 45 years old, the single population is 51.6% and married 48.4%, Bachelor's education is the highest at 36.5%, and the income level of more than 10 million IRI per month has 40.6% of the majority.

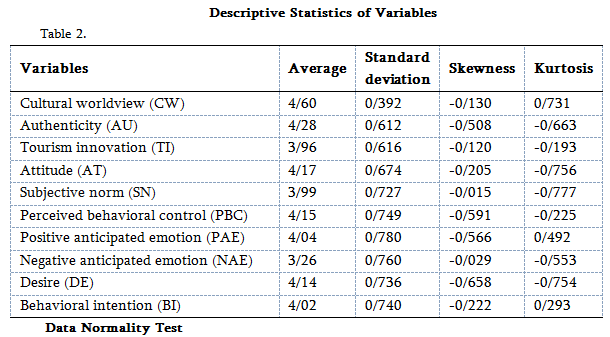

Table 2 presents the statistical summaries of the variables. The average of the variables between 3.26 and 4.60 shows their average status according to the respondents. The standard deviation also expresses the dispersion of responses from the norm in the middle range. Two indices of skewness and kurtosis also suggest that the variables have slight variations from the normal distribution.

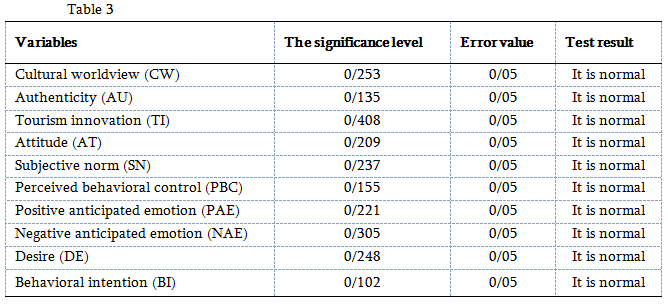

The data's normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test performed with SPSS software. If the value of the significance level in this test is greater than the error value, i.e., 0.05, it can be said that the data is standard by rejecting the H1 hypothesis. Table 3 displays the outcomes of this examination.

Considering the significance level for the variables is greater than the error value, it is clear that the data related to each of the variables of this standard research.

Kolmogorov Smirnov Test Results

Data Fit Test in Factor Analysis

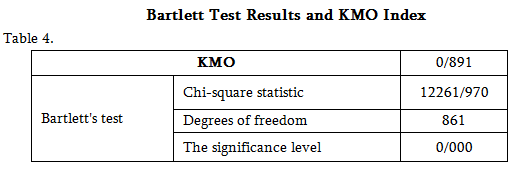

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index, for sampling adequacy, serves the initial purpose of factor analysis. Bartlett's test, like the sampling adequacy index, determines additional variables within the factor model. The outcomes of the data fit test for factor analysis are presented in Table 4.

According to the KMO test outcome, it has a value of 0.89. The research data can be simplified into essential underlying factors, and the sample size is sufficient for factor analysis. Since the level of significance is less than 5%, it can be inferred that at the error level of 5% or the confidence level of 95%, the null hypothesis is not confirmed. So, assumption one means adequacy of the model is accepted. In addition, the amount of chi-square in Bartlett's test (12261/970), which is statically significant at the error level of less than 0.01, indicates a notable dissimilarity between the correlation matrix of the questionnaire items and the identity matrix. It implies that, firstly, there is a strong correlation among the things within each factor. Secondly, there is no correlation between the items of one factor and those of another factor. The outcomes of this test indicate a notable association among the variables, and it is feasible to uncover a new structure within the data.

Confirmatory Analysis of Factor Structure

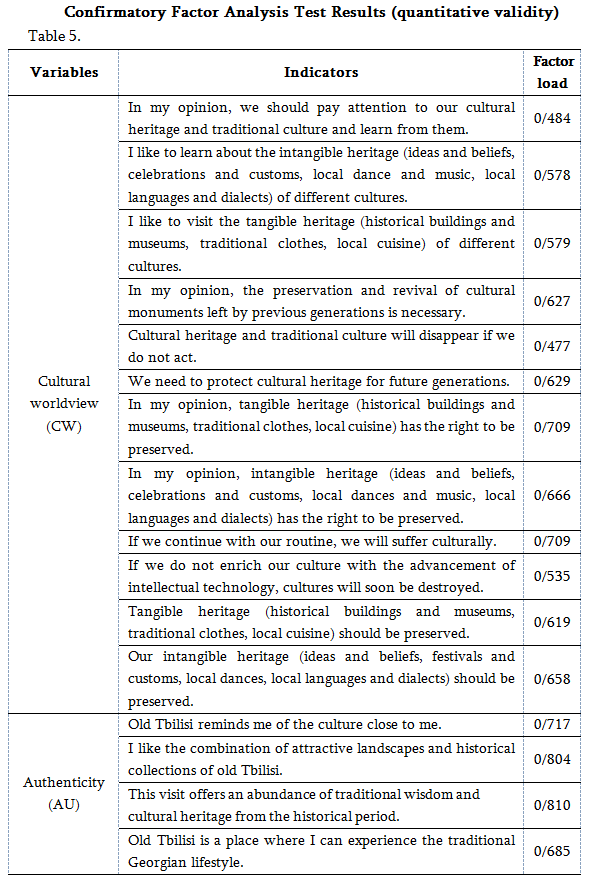

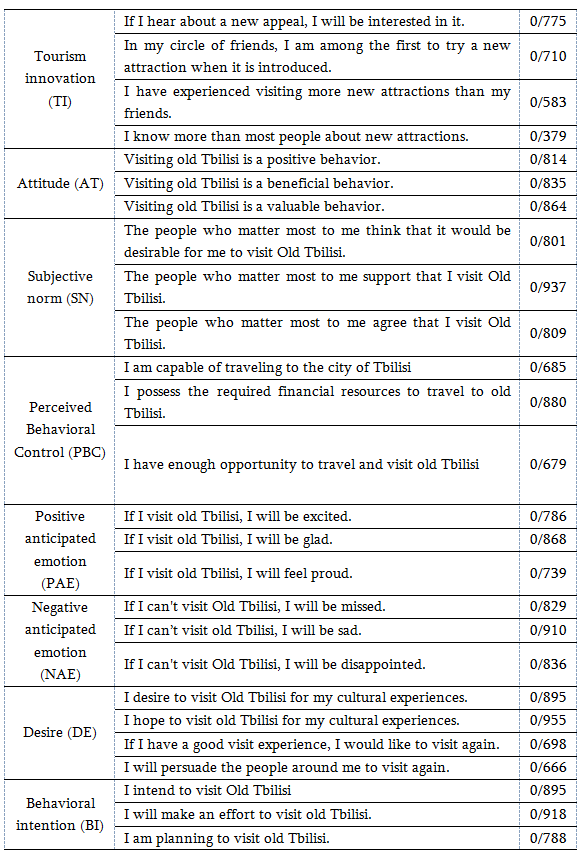

In recognition of the essential requirement for validating the structure being studied and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and that indicators that have a factor load smaller than 0.5 to measure their dependent concept do not have the necessary efficiency and will be excluded from the modeling process; The factor loadings derived from the model of the measurement are displayed in Table 5, organized according to the questions corresponding to each variable. According to the results of this table, it has been determined that all indexes except for indexes 1,5 and 20 had a factor load higher than 0.5. So, they have enough credibility to continue the process of estimation and hypothesis testing.

The fit indices for the measurement model are determined using the chi-square criterion divided by the degrees of freedom (2/243), the softened NFI suitability index (0.982), the increasing suitability index of IFI (0.926), the CFI comparative fit index (0.924), the square root of the approximation error variance estimation RMSEA (0.055) have acceptable values and confirm the good fit of the measurement model.

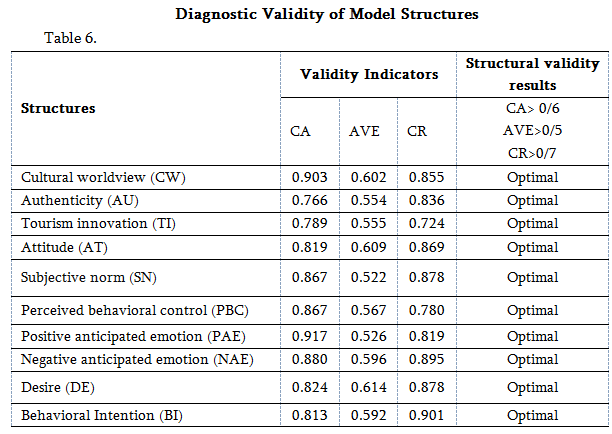

Apart from determining factor loading through confirmatory factor analysis, this research has also examined the diagnostic validity of the questionnaire constructs. This implies that the indicators within each factor should, in the end, demonstrate a distinct and reliable measurement compared to the indicators of other factors in the approach. Simply put, each indicator should effectively capture only its specific factor, and their combination should ensure clear demarcation between all the factors. The procedure was performed utilizing the extracted mean-variance index, which determined that all the structures under study have an average extracted variance (AVE) higher than 0.5, and these coefficients are displayed in Table 6. Eventually, Cronbach’s alpha reliability index was also employed to evaluate the reliability, and the findings are presented in Table 6. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient is used in the structural equation model methodology, and values higher than 0.6 for each structure indicate its adequate reliability (Nanali and Bernstein, 1994).

Structural Model and Testing of Hypotheses

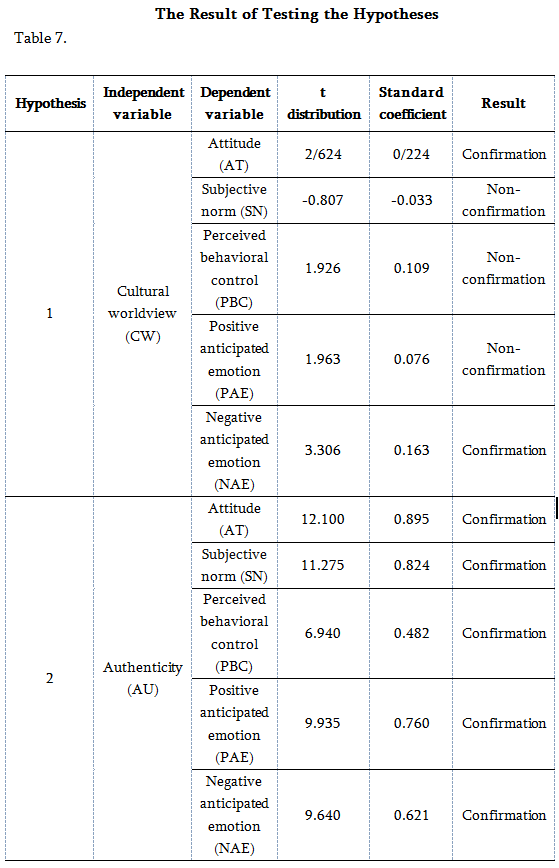

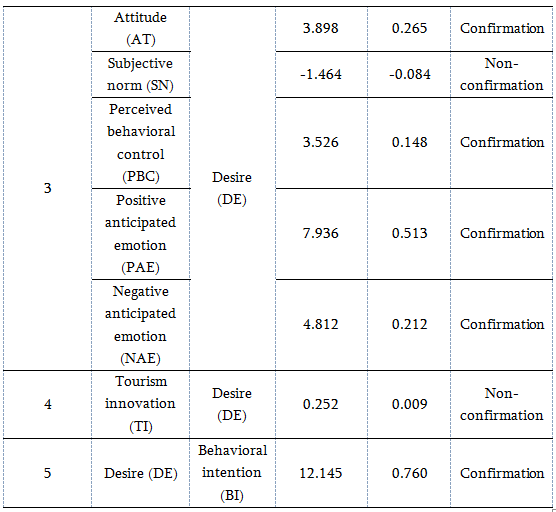

Figure 2 indicates the structural approach was utilized for testing the research hypotheses.

Structural Model Fit Indicators also according to the Chi-square criteria divided by the degree of freedom (2.956), NFI Falling Soft Index (0.959), IFI's increasing fitness index (0.999), CFI adaptive fitness index (0.998(, square root estimation of error variance (0.064), have acceptable values and confirm the suitable fit of the structural model.

Discussion and Conclusion

While CW and AU have been recognized as crucial concepts (Lee et al., 2020), investigations within the field of tourism were undertaken to investigate their effect on the decision-making process for selecting cultural tourism sites through the GBA. Furthermore, various studies have used the GBA and its applications in different areas. Nevertheless, limited emphasis has been given to the significance of CW and AU within the context of the GBA.

The findings of this research suggest that, despite expectations, CW plays a relatively minor role in creating the GBA and creating Behavioral intention for Iranian tourists to visit old Tbilisi. There is no significant impact on the Subjective norm, Perceived behavioral control, and Positive anticipated emotion. Regarding the lack of effect of CW on the Subjective norm, it is possible that tourists under study do not follow much of a collectivist culture. So, there is little pressure from the community and those around them to visit old Tbilisi. Regarding the lack of impact of CW on Perceived behavioral control, it is possible that tourists need more critical variables to control their travel behavior, and AU factors such as CW have little power in this regard. A tangible factor, such as financial ability, is among these interventional variables. Regarding the lack of impact of CW on the Positive anticipated emotion, it can be assumed that motivating the positive emotions of tourists may require more substantial motivational and motivational factors. In general, these results are contrary to Lee et al. (2020). However, it has been found that CW has a notable positive impact on Negative anticipated emotion. Therefore, the more the evaluation and shared beliefs of Iranian tourists about the culture of Georgia are positive and desirable, the more positive the AT of tourists to old Tbilisi. In this regard, Lee et al. (2020) and Choi et al. (2007) have shown a similar result, and Megyeri et al. (2020) have also demonstrated the role of CW and its dimensions on AT of tourists, which is partly in line with the impact of this research. If people cannot travel to Old Tbilisi, their CW can influence their Negative anticipated emotion. The outcome aligns with the results reported by Lee et al. (2020).

However, AU assumes an essential role in comprehending the decision-making procedure of travelers who have experienced Old Tbilisi and affects all the components of GBA. The result indicates explicitly that the experience of pleasant tourism from the old Tbilisi has created a positive Attitude towards this tourist destination and makes an impression on the opinions of others about this tourist destination. It also makes the tourist feel more comfortable traveling to the tourist destination and feel fewer obstacles on this route for them. People predict that their choice to travel to Old Tbilisi creates pleasant feelings that, if they enjoy the experience of past travel to this tourist destination, are more predicted. Finally, people expect that their choice of not traveling to Old Tbilisi creates unpleasant and regretful emotions that, if they enjoy the experience of past travels to this tourist destination, these forecasts will increase. In general, the result indicates that AU successfully elicits genuine experiences among tourists. The correlation between AU and the GBA, considering authentic tourist experiences and their influence on decision-making, makes a valuable addition to the literature on tourism. The outcomes align with the discoveries made by Lee et al. in 2020.

Moreover, it is also determined that Attitude, Perceived behavioral control, Positive anticipated emotion, and Negative anticipated emotion have a positive relationship with the Desire to visit, and significantly, it affects the Behavioral intention as well. The findings also indicate that the Positive anticipated emotion has the most substantial impact on the Desire to visit among other GBA components.

Finally, it was found that TI has no impact on DE to visit. It is likely that for tourists under the study of tourism location, the purpose of this study has no new innovative characteristics because they have already traveled to this place or similar places. Therefore, increasing the sense of innovation does not increase their desire to travel there. The findings of Huseynov et al. (2020), contrary to the result, indicated the significant impact of TI on their Desire to visit the destination. Therefore, this study explores the impact of CW and AU on existing literature, thus improving our comprehension of the GBA in explaining the decision-making process of Iranian travelers planning a visit to Old Tbilisi. It is evident that AU assumes a significant role in describing tourists' behavior in the GBA and better predicts their behavioral intentions. It can be seen that AU’s understanding of the GBA’s cultural heritage is more critical than CW’s.

Practical Suggestions

It is suggested to Tourism Tour Managers in Tbilisi:

• According to the meaningful impact of tourists' CW on AT and Negative anticipated emotion,

a) Knowing how to preserve historic buildings and museums, traditional clothing, foods,

b) Awareness and education of tourists about preserving culture, cultural, and historical heritage.

• According to the noteworthy impact of AU on all elements of the GBA,

a) Offers tourists the chance to explore the traditional history and culture of Tbilisi as part of the tourism experience,

b) In addition, the original attraction of this destination uses attractive images of Tbilisi that reflect the combination of stunning landscapes and historical collections of Tbilisi on virtual pages and tourism websites.

• Considering the significant impact of the components of the GBA on the Desire of tourists to visit the old Tbilisi,

a) To create a favorable Attitude towards the old Tbilisi, to help customers who are more famous and have good communication channels with others to help them show tourism values to this destination,

b) Tourist tours to Tbilisi, in the holidays and leisure times most tourists are planned,

c) In addition, it is possible to pay for tourists in installments to make it easier and more controlled to make this trip.

d) By holding exhibitions to introduce traditional dishes, traditional shows, handicrafts, and other benefits to Georgia to make them feel positive about future trips to this tourism destination,

e) Show the unique benefits dedicated to Tbilisi's tourism destination to strengthen the Negative anticipated emotion so that tourists know what benefits they will lose if they do not travel to this destination.

• According to the meaningful impact of Desire's visit to Old Tbilisi on their Behavioral intention to travel to this destination,

a) Encourage tourists to make these trips by providing virtual trips to the old Tbilisi.

b) When people go to tourism agencies or visit tourist sites, tour presenters provide a clear and clarified image of tourists by providing oral brochures and guidance.

References:

• Ajzen, I., & Driver, B. L. (1992). Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice. Journal of Leisure Research, 24(3), 207–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1992.11969889.

• Bagozzi, R. P., & Pieters, R. (1998). Goal-directed emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 12(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999398379754.

• Bartels, J., & Reinders, M. J. (2011). Consumer innovativeness and its correlates: A propositional inventory for future research. Journal of Business Research, 64(6), 601-609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.05.002.

• Ben-Dalia, S., Collins-Kreiner, N., & Churchman, A. (2013). Evaluation of an urban tourism destination. Tourism Geographies, 15(2), 233-249. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.647329.

• Chhabra, D., Healy, R., & Sills, E. (2003). Staged authenticity and heritage tourism. Annals of tourism research, 30(3), 702-719. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00044-6.

• Chiu, W., & Cho, H. (2022). The model of goal-directed behavior in tourism and hospitality: A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Travel Research, 61(3), 637-655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287521991242.

• Choi, A. S., Papandrea, F., & Bennett, J. (2007). Assessing cultural values: Developing an attitudinal scale. Journal of Cultural Economics, 31(4), 311–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-007-9045-8.

• Choi, A. S., & Fielding, K. S. (2016). Cultural attitudes as WTP determinants: A revised cultural worldview scale. Sustainability, 8(6), 570.

• Couture, A., Arcand, M., Sénécal, S., & Ouellet, J. (2015). The influence of tourism innovativeness on online consumer behavior. Journal of Travel Research, 54(1), 66-79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513513159.

• Crompton, J. L., & Ankomah, P. K. (1993). Choice set propositions in destination decisions. Annals of Tourism Research, 20(3), 461–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(93)90003-l.

• Girish, V. G., & Lee, C. K. (2020). Authenticity and its relationship with the theory of planned behavior: Case of Camino de Santiago walk in Spain. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(13), 1593-1597. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1676207.

• Goldsmith, R. E., & Hofacker, C. F. (1991). Measuring consumer innovativeness. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 19(3), 209-221. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02726497.

• Hamid, S., & Bano, N. (2021). The behavioral intention of traveling in the period of COVID-19: an application of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and perceived risk. International Journal of Tourism Cities. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-09-2020-0183

• Gursoy, D., Ouyang, Z., Nunkoo, R., & Wei, W. (2019). Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: A meta-analysis. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(3), 306-333. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2018.1516589.

• Han, H., & Ryu, K. (2012). The theory of repurchase decision-making (TRD): Identifying the critical factors in the post-purchase decision-making process. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 786-797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm .2011.09.015.

• Han, H., Olya, H. G., Kim, J., & Kim, W. (2018). Model of sustainable behavior: Assessing cognitive, emotional and normative influence in the cruise context. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(7), 789–800. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2031.

• Hirschman, E. C. (1980). Black ethnicity and innovative communication. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 8(1-2), 100-119. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02721977.

• Hoffmann, S., & Soyez, K. (2010). A cognitive model to predict domain-specific consumer innovativeness. Journal of Business Research, 63(7), 778-785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.06.007.

• Huseynov, K., Costa Pinto, D., Maurer Herter, M., & Rita, P. (2020). Rethinking emotions and destination experience: An extended model of goal-directed behavior. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 44(7), 1153–1177.

• Jang, S. S., Ha, J., & Park, K. (2012). Effects of ethnic authenticity: Investigating Korean restaurant customers in the US. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31 (3), 990–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.12.003.

• Kang, B., Hu, Y., Deng, Y., & Zhou, D. (2016). A new methodology of multicriteria decision-making in supplier selection based on numbers. Mathematical problems in engineering, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8475987.

• Kang, S. K., Lee, C. K., & Lee, D. E. (2016). Examining cultural worldview and experience by international tourists: A case of traditional house stay. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(5), 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2015.1062406.

• Kim, E., Tang, L., & Bosselman, R. (2019). Customer perceptions of innovativeness: An accelerator for value co-creation. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 43(6): 807-838. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348019836273.

• Kim, M. J., & Hall, C. M. (2019). Can co-creation and crowdfunding types predict funder behavior? An extended model of goal-directed behavior. Sustainability, 11(24), 7061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247061.

• Ko, S., & Choi, Y. (2020). The effects of compassion experienced by SME employees on affective commitment: Double-mediation of authenticity and positive emotion. Management Science Letters, 10(6), 1351–1358. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.11.022.

• Kolar, T., & Zabkar, V. (2010). A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tourism Management, 31(5), 652–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.01.

• Kososki, M., & Prado, P. H. M. (2017). Hierarchical Structure of Brand Authenticity. Creating Marketing Magic and Innovative Future Marketing Trends, 1293–1306.

• Kountouris, Y., & Remoundou, K. (2016). Cultural influence on preferences and attitudes for environmental quality. Kyklos, 69(2), 369–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12114.

• Lee, C. K., Kang, S. K., Ahmad, M. S., Park, Y. N., Park, E., & Kang, C. W. (2021). Role of cultural worldview in predicting heritage tourists’ behavioral intention. Leisure Studies, 40(5), 645-657. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2021.1890804.

• Lee, C. K., Olya, H., Park, Y. N., Kwon, Y. J., & Kim, M. J. (2021). Sustainable intelligence and cultural worldview as triggers to preserve heritage tourism resources. Tourism Geographies, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2021.2016934.

• Lee, C. K., Song, H. J., Bendle, L. J., Kim, M. J., & Han, H. (2012). The impact of nonpharmaceutical interventions for 2009 H1N1 influenza on travel intentions: A model of goal-directed behavior. Tourism Management, 33(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.006.

• Lee, C.K., Ahmad, M. S., Petrick, J. F., Park, Y.N. (2020). The roles of cultural worldview and authenticity in tourists’ decision-making process in a heritage tourism destination using a model of goal-directed behavior. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 18 (2020) 100500.

• Lee, C. K., Kang, S. K., Ahmad, M. S., Park, Y. N., Park, E., & Kang, C. W. (2021). Role of cultural worldview in predicting heritage tourists’ behavioral intention. Leisure Studies, 40(5), 645-657. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2021.1890804.

• Lee, S. J., Song, H. J., Lee, C. K., & Petrick, J. F. (2018). An integrated model of pop culture fans’ travel decision-making processes. Journal of Travel Research, 57(5), 687–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517708619.

• Li, L., & Buhalis, D. (2006). E-commerce in China: The case of travel. International Journal of Information Management, 26(2), 153-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2005.11.007.

• Liu, H., Cutcher, L., & Grant, D. (2015). Construction of authentic leadership, gender, work, and organization. Gender, Work and Organization, 22(3), 237–255.

• Matsumoto, D. (2006). Culture and cultural worldviews: Do verbal descriptions about culture reflect anything other than verbal descriptions of culture? Culture & Psychology, 12(1), 33–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067x06061592.

• Meng, B., & Choi, K. (2016). The role of authenticity in forming slow tourists’ intentions: Developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tourism Management, 57, 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.07.003.

• Musa, G., Kayat, K., & Thirumoorthi, T. (2010). The experiential aspect of rural homestay among Chinese and Malay students using the diary method. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(1), 25-41. https://doi.org/10.1057/thr.2009.26

• Mutana, S., & Mukwada, G. (2018). Mountain-route tourism and sustainability. A discourse analysis of literature and possible future research. Journal of outdoor recreation and tourism, 24, 59-65.

• Newman, G. E. (2019). The psychology of authenticity. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 8-18.

• Noh, M., Runyan, R., & Mosier, J. (2014). Young consumers’ innovativeness and hedonic/utilitarian cool attitudes. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 42(4), 267-280. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-07-2012-0065.

• O’Sullivan, D., & Strauser, D. R. (2009). Operationalizing self-efficacy, related social cognitive variables, and moderating effects: Implications for rehabilitation research and practice. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 52(4), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355208329356.

• Pavlou, P. A., & Chai, L. (2002). What drivers’ electronic commerce across cultures? A cross-cultural empirical investigation of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 3(4), 240–253.

• Perugini, M., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2004). The distinction between desires and intentions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.186.

• Richards, G. (2018). Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 36, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.03.005.

• Roehrich, G. (2004). Consumer innovativeness concepts and measurements. Journal of Business Research, 57(6), 671-677. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00311-9.

• Shen, S. (2014). Intention to revisit traditional folk events: A case study of Qinhuai Lantern festival, China. International Journal of Tourism Research, 16(5), 513–520. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1949.

• Song, H., You, G. J., Reisinger, Y., Lee, C. K., & Lee, S. K. (2014). The behavioral intention of visitors to an Oriental medicine festival: An extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tourism Management, 42, 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. tourman.2013.11.003.

• Song, H. J., Lee, C. K., Park, J. A., Hwang, Y. H., & Reisinger, Y. (2015). The influence of tourist experience on perceived value and satisfaction with temple stays: The experience economy theory. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 32(4), 401-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.898606.

• Song, H., Lee, C. K., Reisinger, Y., & Xu, H. L. (2017). The role of visa exemption in Chinese tourists’ decision-making: A model of goal-directed behavior. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(5), 666-679. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1223777.

• Thompson, M., Ellis, R., & Wildavsky, A. (1990). Cultural theory. Boulder, Colorado, CO: Westview Press.

• Throsby, D. (2003). 22 Cultural sustainability. A handbook of cultural economics, 183.

• Triandis, H. C. (1989). The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychological Review, 96(3), 506–520. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.96.3.506.

• Wei, C., Dai, S., Xu, H., & Wang, H. (2020). Cultural worldview and cultural experience in natural tourism sites. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 43, 241–249.

• Wei, M., Bai, C., Li, C., & Wang, H. (2020). The effect of host-guest interaction in tourist co-creation in public services: evidence from Hangzhou. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(4), 457-472. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2020.1741412.